Though just a few years old, the Global Public Health Program at Boston College has established itself as a unique presence on campus.

From making video public service announcements about issues facing college students, to serving rural communities in Ecuador, students in the program learn about public health in a powerfully hands-on and interdisciplinary way.

The Global Public Health Program at BC starts with courses that introduce students to public health topics domestically and around the world. In addition to the three-course sequence, the program also helps students pre-professionally through events like the STEM Career Fair, alumni panels for students interested in the master’s of public health degrees, research opportunities, and partnerships with the Office of Health Promotion, the Career Center, and clubs like BC EMS.

Faculty in the program aim to expand students’ awareness of health as a global social justice issue, not just help them pursue interests in public health.

Joyce Edmonds of the Connell School of Nursing co-teaches the two courses Public Health in a Global Society and Contemporary issues in Public Health. She explained that the program’s founding vision included three goals.

“It’s global, it’s interdisciplinary, and it has a strong ethical foundation,” Edmonds said. “It’s building on the strengths of our BC community.”

To that end, each course is co-taught by faculty from CSON and the Lynch School of Education or the School of Social Work. According to Kimberly Austin, a graduate of the program who is now enrolled in BC’s direct-entry nursing program, Edmonds often shared stories of her experience working with patients as an R.N. Guest speakers from departments such as economics and communication also emphasize how multifaceted the field of public health is.

Meanwhile, Summer Hawkins, who teaches in the School of Social Work and co-teaches with Edmonds, brings a slightly different, informatics-minded approach, again speaking to the diversity of the program.

“I bring the perspective that we always need to be collecting data and using that to inform our public service programs and policies,” Hawkins said of her responsibilities. “It creates a wonderful contrast.”

Nicholas Raposo, a former enrollee in one of the introductory courses last year and CSON ’17, agreed that this contrast enriched his experience. His experience with the program exhibits the interdisciplinary liberal arts values that the classes hope to embody.

“Once I realized how interconnected the web of health actually is, I began to understand how different parts of my education fit together,” he said.

He also learned that health is not always related to a germ or to genetics, but is shaped by our environment and habits.

For example, students pick a topic such as sleep or healthy eating that relates to their lives as college students. They then write and film PSAs to raise awareness of these issues. Hawkins and Edmonds described this project as a highlight of the course because it is an opportunity for students to be creative, but also connects to issues that impact their daily lives.

This focus on the social determinants of health strongly relates to BC’s values of social justice. In the third course, Public Health Practice in the Community, Austin volunteered at an elderly center in Allston-Brighton and explored how certain factors, such as transportation, affected that community.

“Every single class, we talk about health disparities,” Hawkins said. “Why is it that certain groups are at higher risk and what can we do to address that?”

The program also encourages students to address current issues beyond BC. Austin’s class discussed the impact of Affordable Care Act policies on nursing.

Hawkins noted that when her class studies cholera epidemics, students often think issues remain in the past, when in reality, they are still problems.

While students in the Global Public Health Program have majors as diverse as biology, education, and management, and go on to many different paths in research and graduate school, they share a common understanding that health is not an isolated issue.

When Raposo started his clinicals for CSON, he felt helpless because there was little he could do for his patients, who were often in poor health by the time they arrived at the hospital.

“I realized that I can do the greatest good for my patients in primary care: helping to promote and maintain health,” he said.

Similarly, although Austin already planned on applying to medical or nursing school, the program had a powerful influence on the kind of practitioner she wanted to be.

Now, she works at a flu clinic as part of her graduate program, and she feels more attached to her work because “these issues are at the forefront of people’s lives.”

Professors hope to develop the Global Public Health Program into a minor and even a major at BC. According to Edmonds, the student demand is there. She aims to engage more faculty in the program.

“I didn’t even know what public health was as an undergrad,” Hawkins said, but “if there’s one thing I’d want students to take away, it’s that public health is everywhere.”

Correction: This article has been edited to reflect that a quote mistakenly attributed to Professor Joyce Edmonds was actually said by Professor Summer Hawkins. The study abroad program in Ecuador is also arranged through the Population Health Nursing course, and is not specifically one of the 3-credit global public health courses as his article had suggested previously.

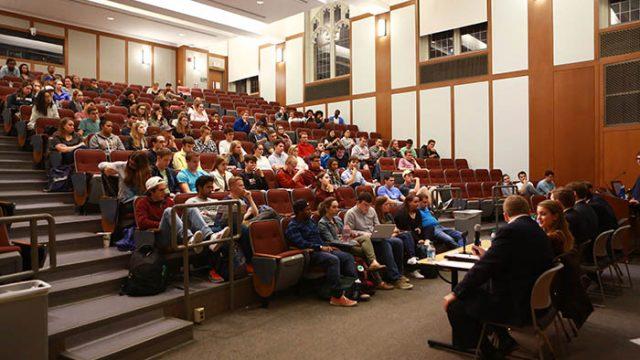

Featured Image by Yi Zhao / Heights Staff