The expectation to get an elite internship induces in undergrads an existential crisis similar to the one caused by the college process, but instead of Harvard, Yale, and Boston College, now it’s now J.P. Morgan, Conde Nast, and Goldman Sachs.

Suddenly, we’re defined not just by the clothes we wear and the schools we attend, but by the companies for whom we make photocopies and fetch coffee, if we’re lucky.

One’s ability to feed his family 15 years down the line appears to rely on one cover letter to be a social media intern at one of the thousands of companies in Manhattan–a fear that haunted no one for all of human history, until 10 years ago.

Last month, after making a LinkedIn account and doing my best to divide my worth into categories like Education, Experience, and Skills & Endorsements, I applied to a myriad of positions with words like “Marketing” and “Public Relations” in the titles.

I received a prompt response from a startup with ambiguous details online that led me to believe it was a New Age marketing firm—the kind of description at which others raise their eyebrows and say “wow,” with evocations of Silicon Valley.

I went in for the first interview on the day after Easter, to its office on 35th and 8th in the bowels of a Manhattan neighborhood called Hell’s Kitchen, a detail which in hindsight is now painfully coincidental.

Up I went in the gold-plated elevator to the 19th floor and when the doors opened, I was greeted by upbeat, millennial rock music that hinted there might be yoga balls instead of chairs and craft beers on-tap instead of water coolers.

I checked in at the front desk, and soon, a man, who looked like FUBU CEO and Shark Tank investor Daymond John, but with a British accent, called my name and introduced himself as Mikey. Mikey complimented me for my pocket square and said I looked sharp. I smiled and yearned for even more acceptance.

In his office, he asked why I was interested in a marketing internship and instead of honestly saying, “to prove my worth to my peers and parents,” I presented my pre-written response about my love for words, both how they’re employed and interpreted and blah blah blah.

He smiled, then told me how the company had raised $10,000,000 in ad revenue for the Humane Society of the United States in just the past year and it is looking to open up five more offices in the next year, boosting the revenue to $50,000,000.

Now, mind you, I passed Finite Problems and Applications last semester by the skin of my teeth. My most business-oriented skill is my ability to compellingly argue a Marxist literary criticism of Frankenstein.

How does one raise ad revenue? With the help of interns, I assumed. And how does one open more offices? Well, by generating more revenue and hiring more interns, of course.

He let me know I’d be notified later if I was selected for a second-round interview.

I got home and received an email from the CEO, Jill, who told me, “We want to invite you to come see us “naked” … well… The bare bones of what makes us unique. We have arranged for you to spend the day with us on 4/03/2018. Like we said it’s just an insight to our normal day-to-day with the teams and our live campaigns.”

The next morning my mother dropped me off at the Metro North station where I joined the other working professionals waiting for the train to Manhattan. I got on the 8:09 express train, strictly for business people in business attire going into the city to do business.

In Grand Central Station, with 40 minutes to kill, I joined the brigade of bankers at the shoeshine stand and examined the front page of the Wall Street Journal while the knock-off Gucci loafers I bought at a thrift store received a glistening polish as bright, I hoped, as my future.

I went to the same office and sat in the same waiting room but this time my name was called by a man, Leander, who said today we would be going downtown.

Hopeful and enthusiastic, I thought downtown referred to another office, or maybe a client’s headquarters. We road the R train downtown and got off at Lafayette Street near New York University.

When we exited the car, he pulled me aside and told me take notes, as he explained the Law of Averages—which states for every 33 people engaged with “experiential” marketing, one of them is guaranteed to be a customer.

I didn’t know what experiential marketing was but I was too afraid to ask. Leander then had me write down a list of interview questions: What are 10 strengths and 10 weaknesses, what would a letter of recommendation say, who are some role models, and lastly, what’s a product I would design and how would I market it?

He then told me to go stand in the corner of the subway platform and that he would be back to check on me. I gave great thought to my answers and invented a product with an elaborate marketing campaign—it’d be like a Tide stain stick, but for shining shoes.

First, in front of the shoeshine stand in Grand Central, we’d organize a flash mob to use the product while all the business people paid $10 for a single shine. Then we’d put posters on the trains for the businesspeople to see. We could also give free samples at high-end shoe stores in the city.

While I was designing my business plan, Leander paced back and forth on the platform with an iPad in hand, asking, “Excuse me sir/miss, do you like puppies?” Nobody said yes, but if they had, Leander would have asked if they wanted to donate to the Humane Society.

It then occurred to me: “Is experiential marketing just pestering people on the subway?”

Leander came over, approved of my answers to his initial questions, and then gave me five more “tasks,” as he called them, asking me to reflect on 20 qualities of a leader and to list times in my life when I’ve exemplified these qualities.

He then returned to “marketing”, hoping to find people naive enough to swipe their credit cards in the iPad of a stranger in the subway.

After watching him receive rejection after rejection, he finally said it was time for lunch. He said we’d be going to Chipotle and the thought of a free burrito quelled my suspicions about the legitimacy of the company.

One would think a marketing firm conducting a nine-hour interview would provide lunch to its applicants. But alas, I paid for my own food, and I got a bowl because I didn’t think a 5-pound burrito was appropriate to eat on an interview.

We sat down and I asked Leander to tell me more about the internship responsibilities, but he dodged the question by saying he’d give me a business breakdown later on.

I then asked how long he had been working with the company. He said two months, and before that he taught chess to schoolchildren. He said he was once ranked top 10 in the country when he was a kid.

And here he was now, on a lunch break from asking for money in the subway. I asked if we were going back to the office after lunch, but he said we’d be going back into the “field.”

Naive and desperate for an internship, I told myself that this was a test to throw me out of my element, that there was definitely a real internship at the end of this smog-colored rainbow.

We returned to the platform, and Leander gave me more tasks. This time he wanted me to consider the differences between salary, wages, and commission.

As he walked away, the word “commission” rang in the air like an express train running by, and I finally admitted to myself that it was a scam. I wrote the pros and cons of the different payment options and purposefully omitted pros to working for commission.

I called him over to check my answers and he then told me about all of the wonderful perks of working for commission—how it rewards employees for their performance and eliminates the possibility of workers slacking off. He then informed me interns were paid entirely with commission. The only way to make money as an intern was to be more successful than Leander and coax people into “donating” on the way to work.

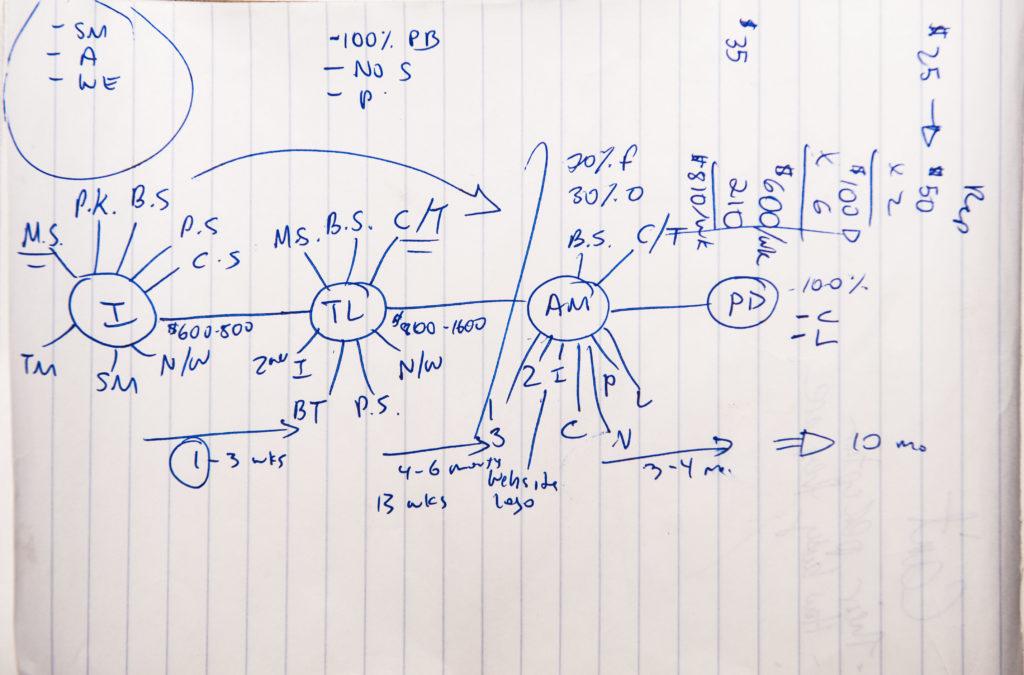

I bluntly asked him if this internship was just begging in the subway. He then asked for my pen and paper and drew out an elaborate business model (see image above) and explained how the logistics of the company.

For every $25 donation Leander solicits for the Humane Society, he earns $50 dollars. Enticing, I know. That math is almost too good to be true. And, if I worked hard enough, he said, I could be promoted from intern to a team leader in one to three weeks, at which point I would be responsible for more interns.

He solidified his pitch by adding that he had recently travelled to Phoenix and Cleveland for the company, and that sometimes interns traveled.

Oh, how I’ve always wanted to see the world.

Leander then said he thought I had the brains and the people skills for it, but he was not sure about my attitude.

After standing in a dusty subway corner all day, I looked at him calmly and said, “well, I’ve been standing in a G.D. subway station for 7 hours.”

He stared at me, stunned, as if no other applicant in the past had called him out for who he really was: a scheming, cheating, time-wasting, pathetic excuse of a marketing employee who, at 27-years-old, was essentially begging for money in the subway station, and wanted to trick others into joining.

I delivered a tongue-lashing harsh enough to clean the grime off the tiled walls I’d leaned against all day. It made me feel better, but I never should have been in that situation to begin with.

My most egregious mistake was standing there for six hours. I was blinded by my desire for a “real” job and, regrettably, was willing to surrender my dignity to earn one.

I think I’ll just caddy this summer.