Thursday night, out of a fleeting curiosity, I turned on the Rams-Vikings Thursday Night Football game to catch a glimpse of the NFL’s best offense through three games of the season. And what I saw did nothing to dispel that notion. Watching the Rams and brilliant young head coach Sean McVay light up the scoreboard was one of the impressive things I’ve seen on a football field in a long time. Sure, the Rams have talent, but most NFL offenses have talent. What made the Rams so impressive was how well-coached they were. McVay’s brilliant play designs maximized mismatches, presented Goff with easy throws, and kept the defense off balance all night.

Watching that game was a reminder of one of the sometimes-forgotten truths of football. Coaching should be judged on how it utilizes the talent it has. A good coach puts the players he possesses in the best position possible to succeed. Look at Chris Petersen, who coached Boise State to one of the biggest upsets in college football history against an Adrian Peterson-led Oklahoma and is now plying his trade at Washington, or David Cutcliffe, whose Duke team is 4-0 despite losing starting quarterback Daniel Jones to injury for two games. McVay is one of the premier examples of this truth. He transformed Goff, who looked lost in eight games under Jeff Fisher, into one of the best young quarterbacks in the game.

Bad coaching? Bad coaching makes it more difficult for players to succeed. And that’s what was on display in Boston College football’s game against Temple, and has been on display for six years. To be fair, the Eagles have been a good defensive team during this time, and much of that is due to Don Brown and Jim Reid. The same can’t be said for offense and special teams. Consistently, throughout Steve Addazio’s tenure, he and his coaching staff have failed to put his team in a good position to succeed on those fronts, and they need to be held more accountable.

Part of what makes McVay and the Rams offense so good is their willingness to improvise on all downs. They are never stuck to a set formula and love to pass on first down to keep the defense guessing. Addazio, on the other hand, was extremely predictable against Temple. BC ran 35 first down plays against the Owls, excluding Anthony Brown’s kneel down in the fourth quarter—27 of those were runs. In other words, 77 percent of the time on first down, the Eagles ran the ball. It continued on second down. BC ran the ball on 66 percent of second downs, and was even more predictable on second and five or less. In those situations, it ran the ball on 8-of-10 plays. That’s 80 percent.

Now, given that the Eagles were up double digits for most of the second half, a more run-heavy attack would be understandable, but this isn’t just a one-time occurrence due to game flow either. Look at BC’s play-calling tendencies from its loss against Purdue. The Eagles ran 11 first down plays while they were within two scores of the Boilermakers and ran the ball on seven of them. They faced 11 second down plays in the same time frame, and ran on seven of those. Sixty-three percent of the time the Eagles ran the ball on first and second down, and the Boilermakers played like they knew what was coming, presenting a stacked front that A.J. Dillon and Co. were stymied by time and time again. The longest gain on one of those plays for BC? Six yards, on a jet sweep to Jeff Smith.

And, as most Eagles fans will know, this is something that has been a hallmark of play-calling during Addazio’s tenure. His traditional run-first approach appears too conservative at times, and looks especially inadequate against the best teams. Take the 2016 Red Bandanna game, where BC, already 0-2 in conference play, hosted Clemson, the eventual national champion. Like any underdog, the Eagles’ best hope to win the game was an ultra-aggressive approach complete with a sprinkle of good fortune. Instead, BC ran on 59 percent of its first downs and 72 percent of its second downs in the first half against one of the best defensive fronts in the country. No shocker, it found itself trailing, 21-3, at halftime—and wound up losing, 56-10.

And sometimes, it doesn’t even work against bad teams. Take the 2015 game against Wake Forest, which the Eagles lost, 3-0. You can look at that game and say that BC would have won if Colton Lichtenberg hadn’t missed two chip-shot field goals. That might be true, but you know what doesn’t help your team’s winning chances? Running on 82 percent of first downs and 74 percent of second downs, despite averaging just 3.63 yards per carry.

Sure, the Eagles rotated between Troy Flutie and Jeff Smith, two quarterbacks with a combined 55 career completions and 719 yards, under center that day, and the two of them combined to go 6-of-20 for 74 yards. The offensive staff certainly didn’t make it easier for them. The duo dropped back to pass 19 times on second and third down. They faced a down and distance of less than six yards three times. It’s even worse if you consider third down. On 10 combined dropbacks, the two of them faced third and less than six just twice. The average distance they had to gain was 10.2 yards. Asking even the best quarterbacks in the world to consistently convert third and longs is a foolish endeavor, and consistently putting Flutie and Smith in that situation because of an insistence on relying on a questionable running attack is inexcusable.

Well, what if BC just didn’t have the right personnel to execute Addazio’s run-heavy philosophy that day? After all, the Eagles didn’t have an Andre Williams or an A.J. Dillon carrying the rock against Wake Forest, instead relying on Marcus Outlow and Tyler Rouse to shoulder the majority of the carries. BC’s lackluster defeat to Purdue serves as a counterpoint to that argument, but if that’s not convincing enough, what about an embarrassing 34-10 defeat to then 2-5 UNC in 2014 where the Eagles ran on 79 percent of first downs and 63 percent of second downs, continually forcing Chase Rettig into third and long situations that were untenable: On that day, the average distance Rettig needed to gain when dropping back on third down was just seven yards, still a tall ask for any quarterback to consistently convert.

The list of games where the offensive strategy has made it more difficult than necessary for BC to win football games goes on, but the questionable coaching decisions don’t stop there. During Addazio’s tenure, the Eagles have consistently failed on all aspects of special teams, giving up free points thanks to dropped snaps, poor punt blocking, or missed field goals. This season, BC has allowed three blocked punt returns for touchdowns, has missed four extra points, and fumbled twice on kick returns, making wins over Temple and Wake Forest much closer than they needed to be.

And that’s just 2018. Look at prior years, where a missed extra point in overtime cost BC the 2014 Pinstripe Bowl, or the aforementioned Wake Forest game, where the Eagles would have won despite all the poor offensive decision-making if they had a kicker that was able to make a field goal just barely longer than an extra point. It’s easy and fair to blame the players for some of the misses. After all, it’s not unreasonable to expect a college kicker to make a 26-yard field goal. But if the kicking game—and all the special teams units—have consistently been a problem for six years, then some of the blame has to go to the coaching staff and the four special teams coordinators the Eagles have had the past six years for not making a more concerted effort to look at the issue and find a solution.

Besides, excuses about personnel, or Addazio’s favorite, youth, are certainly invalid when it comes to coaching ability. As we have already established, a good coach gets the most of the talent they have instead of holding it back. Maybe BC didn’t have a Deshaun Watson or Lamar Jackson under center in past years, but even those two star ACC signal callers would have had a hard time winning games when they were asked to repeatedly convert on 3rd-and-10, or if the team they were playing against was gifted seven points because of a botched punt coverage.

This year has been particularly infuriating because this may be the most talented offensive team and the worst the ACC has been football-wise in the Addazio era. Every team in the conference looks vulnerable except Clemson, and now even the Tigers have a question at quarterback. And on the Heights, the Eagles returned 81 percent of their offensive production from 2017 (according to SB Nation). Dillon is a bonafide star at running back, the offensive line is experienced and tough, Michael Walker, Jeff Smith, Tommy Sweeney, and Kobay White form a solid pass-catching crew, and despite his inconsistencies, Brown is certainly an upgrade over Darius Wade, Jeff Smith, or John Fadule.

And yet, after the best performance of Brown’s career, where he threw for 304 yards and five touchdowns against a Wake Forest team—a point in time when BC looked ready to finally morph into a more balanced team offensively—the team inexplicably went back to its old ways against the Boilermakers, futilely sending Dillon crashing into waves of Purdue defenders who knew exactly what was coming before dropping Brown back to pass on third and longs expecting him to heroically keep drives going.

As the sophomore Heisman hopeful forlornly sat alone on the sideline at the end of the game, knowing the national attention surrounding the BC football team was likely to vanish in an instant, it was hard not to feel sorry for him, because so little of what had transpired that day was his fault. No running back in the world can succeed if they are expected to break two or three tackles a play just to get back to the line of scrimmage. Just imagine what Dillon could do if the Eagles were not so insistent on running him into stacked boxes every first down. We saw glimpses of it during the Wake Forest game, when BC finally mixed some play action in and tore the Demon Deacons to shreds. Now think of that on a weekly basis: an offensive scheme that mixes run and pass equally, showing different looks to a defense on a regular basis, both reducing the ability of defense to sell out for the run, thus giving Dillon easier running lanes, and opening up more easy throws for Brown.

Sure, BC’s current approach will work against UMass, Holy Cross, Temple, or even teams like Wake Forest and Virginia, who the Eagles rolled over at the end of last season. But it’s infuriating to watch this team, and specifically its coaching staff, consistently make winning more difficult than it needs to be.

It is so easy to visualize what BC could be: A team that cuts down on special teams mistakes so it can comfortably defeat the Temples and Wake Forests of the world—a team that’s offensive strategy allows it to compete with the top opponents in the ACC instead of a conservative attack that puts it at a disadvantage against good defenses. Unfortunately, as the past six years have shown, BC fans probably shouldn’t hold their breath waiting for their dreams to come true.

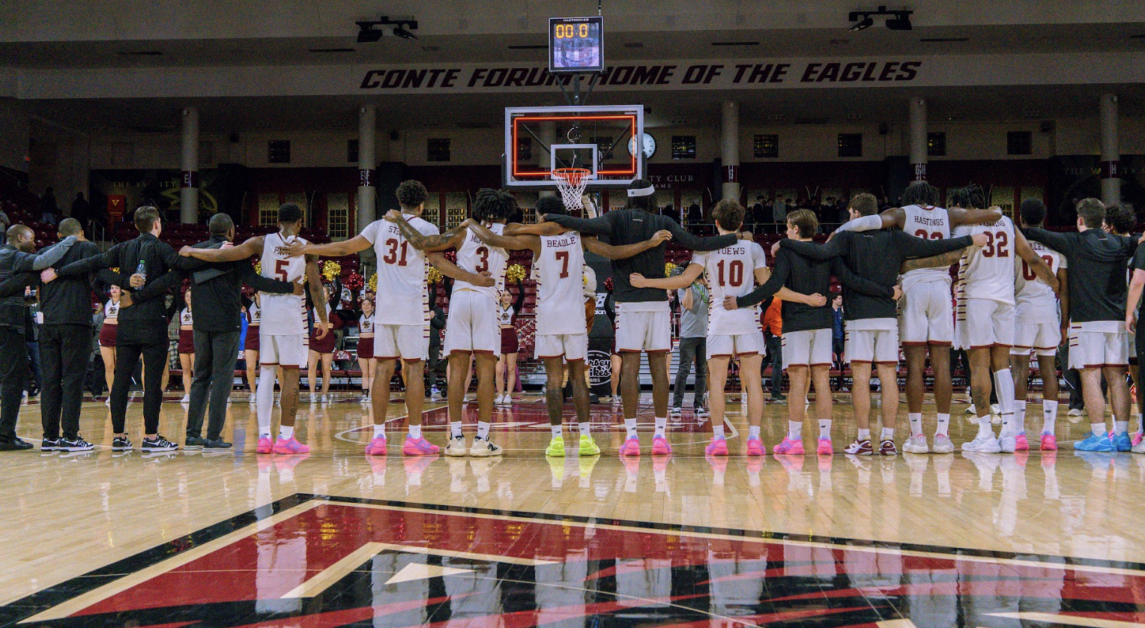

Featured Image by Kaitlin Meeks / Heights Editor