It’s a Sunday evening in October. My roommates and I are lying on our living room floor kind-of sort-of completing the weekend’s homework. In the background is the soft hum of Bon Iver on my hot pink Crosley turntable. The record player sits on a small stand by the window under a framed Vampire Weekend album, which we felt completed the retro aesthetic we’d planned for the space.

Under the stand is a shelf where we keep our small assortment of records. I got most of my records from my father’s college collection of classics—The Stones, The Smiths, The Beatles. I ran across them while packing for school one summer, and decided they’d make good wall art for my dorm room. These records lived on my wall. They were purely art—concert posters would have had the same effect, but there’s something about owning a vinyl that a CD just can’t replicate.

My interest in my father’s records came a few years after the original hipster vinyl revival, which began sometime between 2006 and 2009, almost 50 years after its prime. While the record’s origin spans back to the 19th-century gramophone, its heyday was in the ’60s and ’70s, when rock ruled the country and hippie culture fueled the music industry.

The 12-inch 33 1/2 RPM, long-playing record became the standard analog sound storage medium, and every record label around the country adopted it. Records were the best consumer-grade music people had access to, until CDs came along. When this happened, most big labels stopped producing LPs and converted completely to CDs, causing a momentary death of the vinyl record.

Shortly after finding my dad’s collection, I remember Googling “record stores near me.” My best friend and I spent a summer afternoon driving around Minneapolis looking for these stores, only to find few still in existence. We went to a store called the Electric Fetus, where I purchased my first vinyl—Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago. I’d listened to the album more times than I could count on iTunes and Spotify, but to hold it in my hands, to make the exchange of cash for the music, brought a certain physicality to music that I’d never felt before.

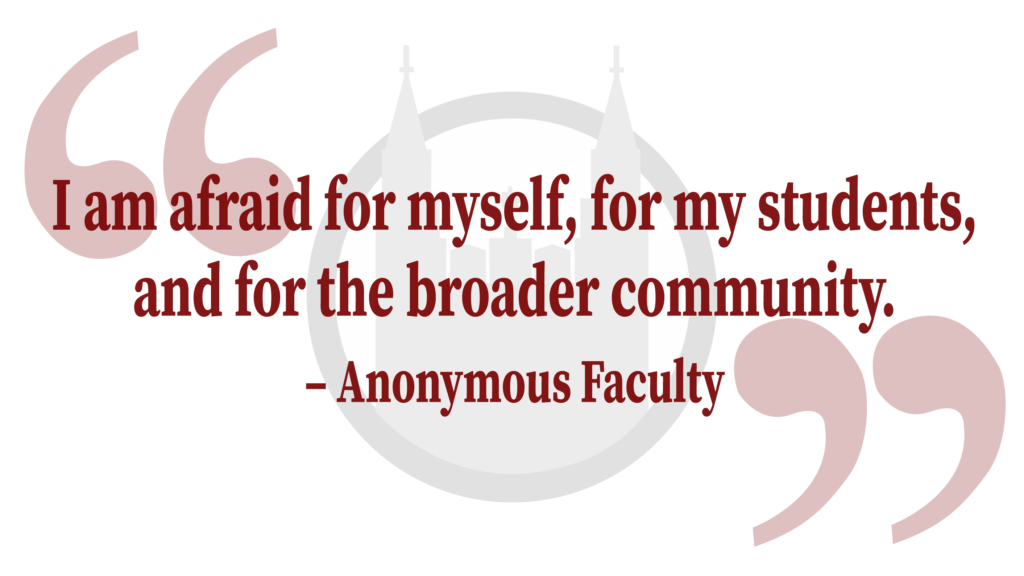

It’s no question that people are buying more vinyl, but their reasons for doing so are the bigger cultural phenomena. There appear to be three main reasons for buying vinyl—nostalgia, sound quality, and aesthetic. With these sects there also seems to be an age divide. Older people tend to buy vinyl out of nostalgia or dissatisfaction with digital sound quality, while younger people tend to enjoy the aesthetic of the record’s album art and the counterculture associated with it.

The nostalgia makes sense. As CDs continue to die out and digital music dominates the industry, people who grew up in the ’60s and ’70s yearn more and more for the music of their youth. My dad often reminisces on the romance in saving up a month’s allowance to buy a record, and the novelty in placing the needle on the vinyl to watch it play. These are childhood memories, and it’s only human to wish for the innocence of childhood in the stress of adulthood. As far as sound goes, there’s great debate about vinyl versus digital sound quality. It’s hard to deny that the record has a fuller, more embodied sound than a track on a computer. There are imperfections in vinyl, a soft crackle in older records, a scratch here and there, that add a unique character to something that contemporary technology has perfected. More than the sound, though, is the experience of listening to an album from start to finish. Most albums are still written with this intent, but are rarely listened to this way.

With Spotify and iTunes and Pandora, it becomes less and less common to sit down and listen to an album all the way through. People create playlists of audio files that they don’t even own, mixing songs from Kanye to Frank Sinatra to The Alabama Shakes all in one sitting. The listening experience has drastically changed. A large portion of today’s American music-loving population never grew up listening to vinyl on a record player. They were given an iPod at age 10, and began curating playlists. Upon discovering the turntable, contemporary music aficionados have developed an appreciation for listening to music the way it was written, thus prompting the purchase of records.

When I purchase these records, I physically own the music. It gives a feeling of particular permanence to my music that I’ve never felt with my digital library or even with my CDs, which are just printed digital copies anyway. In the digital age, analog becomes the novelty. There’s a generation of people that have never owned music in the way you own music with a vinyl record, which is perhaps why its popularity is increasing at such a rapid rate.

Placing For Emma on the Crosley and carefully lifting the needle to the edge of the record, I am prepared for an experience. I let go of the needle as it glides over the shiny black disk, crackling for several seconds before the music begins. One song flows into another and the album tells a story—exactly how Justin Vernon wrote it. No shuffle. No skipping. The album bleeds heartbreak, solidarity, sadness. I’ve heard it thousands of times on my computer, but it wasn’t until I listened to the record that I understood the story, the artist’s intent. I have songs that I like more than others, and will continue to listen to them on my various playlists at the perfect sound quality Spotify Premium provides. But it is nice, once and while, to just sit and experience a musical artifact that has climbed back to the forefront of American culture.

Featured Image by Kelsey McGee / Heights Editor

yo • Nov 15, 2016 at 2:31 pm

crosley’s will ruin your records. it is so worth the investment to buy a proper turntable…for sound and value,

maestro214 • Oct 24, 2016 at 5:26 pm

Please, stop calling records “vinyls” . They are made of vinyl. It’s maddening to a serious lover of records to hear that.

Michael Ellis • Oct 24, 2016 at 3:34 pm

It kind of defeats the whole purpose of vinly to play them on a dreaded Crosley

maestro214 • Oct 24, 2016 at 5:27 pm

Ain’t that the truth!!