I have tragic news for you today, and it may as well signal the end of the world. The Hellmouth has opened, the demons are out to devour us all, and the immortal dead will descend to suck the lifeblood out the world as we know it. That’s right, the beloved television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer will be leaving Netflix this coming weekend, and some of us are more horrified of this fact than others. Yes, I know the show ended in 2003, and that likely makes this a dated pop culture reference. There are always brand new shows available to consume faster than the speed of light, which to some might render older shows irrelevant. But this is no ordinary show. And it’s not about vampires per se, because that would just be obnoxious. Although I don’t think powerful television heroines will ever go out of style, I fear the younger masses will never grow to appreciate a well-made installment in the tradition of vampire lore beyond the unfortunate curiosity that is The Twilight Saga.

But one of the crazy things about my irrational attachment to this show is the fact that its episodes are scary and dark sometimes, and I’m someone that can convince myself that a bump in the night is really a deranged serial killer storming into my house. I used to detest the horror genre. I saw a few episodes of The Walking Dead once and proceeded to stay up till sunrise several nights in a row, because there was just no way I was going to risk being consumed by zombies in the dead of night. Nevermind the fact that a zombie apocalypse was not actually in the midst of unfolding outside the realm of fiction. The show drew upon visceral fears relating to threats to survival and disgusting deformations of the human form, and effectively turned me into a sleep-deprived zombie myself. And Buffy doesn’t shy away from accosting the viewer with vengeful monsters and horrific plotlines that somehow manage to wreak havoc on Sunnydale High School students to a comical extent.

What compelled me to keep watching a show that occasionally made me jump out of my skin was that there was something refreshing amidst elements of the grotesque. You can feel the desperate fear and frustration of Buffy as she angrily crushes what’s left of a vampire that almost single-handedly destroyed the world. You feel the blistering irritation when Xander impulsively pursues situations that are out of his depth on the basis of protecting his pride. Viewers saw common familial or coming of age scenarios appear in the context of witchcraft and evil, and as such enticed them to receive the show’s interpretation of these common phenomena that made sense in their own way. The appealing quality of Buffy made it feasible to keep up with the show’s personable characters and adventurous world, even though I had to creep around corners to make sure no psycho vampires were lurking nearby.

There’s something quite satisfying about taking one’s own emotions out on a leash, which is very often possible through thoughtful storytelling. In their own lives, people sometimes find emotions to be inconvenient or exasperating, because no one wants to sift through that mess to come up with a coherent ordering of those pests that doesn’t involve a lot of self-deception or selective acknowledgement of fact. But fiction can simulate aspects of the real world and present characters and storylines that are familiar enough to our own world that we gravitate toward them. While it may seem like a story imposes a set of ideas or emotions onto the viewer, more often than not it actually just draws out the viewer’s personal response to it. There doesn’t seem to be anything at stake when viewers get mad at a fictional character, or laugh with them at their amusing conversations, or become agitated as the characters are put through the wringer. After all, the viewer’s reactions are just inconsequential responses to a TV show, not uncovered glimpses into their own attitudes and beliefs, right?

Viewers may think those reactions are firmly under their thumbs. But in actuality, fiction may just draw our attention to those responses and make us confront them. And letting those emotional and ideological responses free allows them to take on a life of their own, which makes them very powerful indeed.

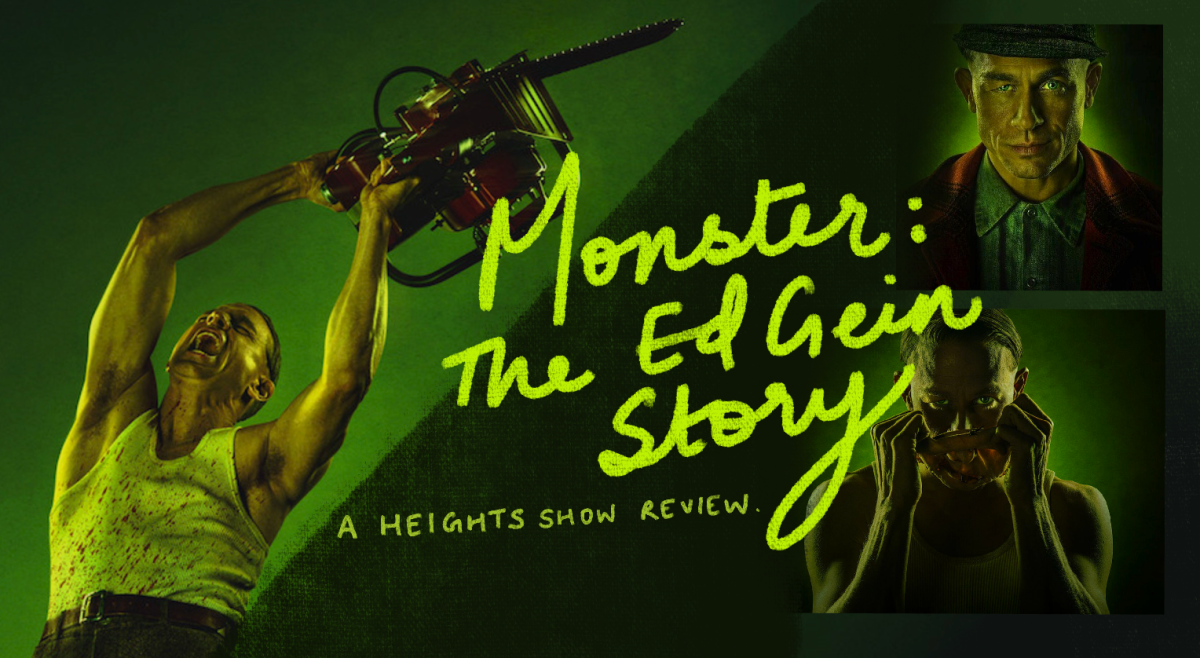

Featured Image by 20th Century Television