Rikers Island, one of the most notorious prisons in America, is connected to the Bronx by a single bridge. While incarcerated, Robert Hinton would watch planes pass by the Empire State building through the window in his cell, wondering what tropical island or foreign location that mere speck of metal was travelling to. Likewise, how might the plane’s passengers see the solitary island on which Hinton, along with 10,000 other people, are imprisoned?

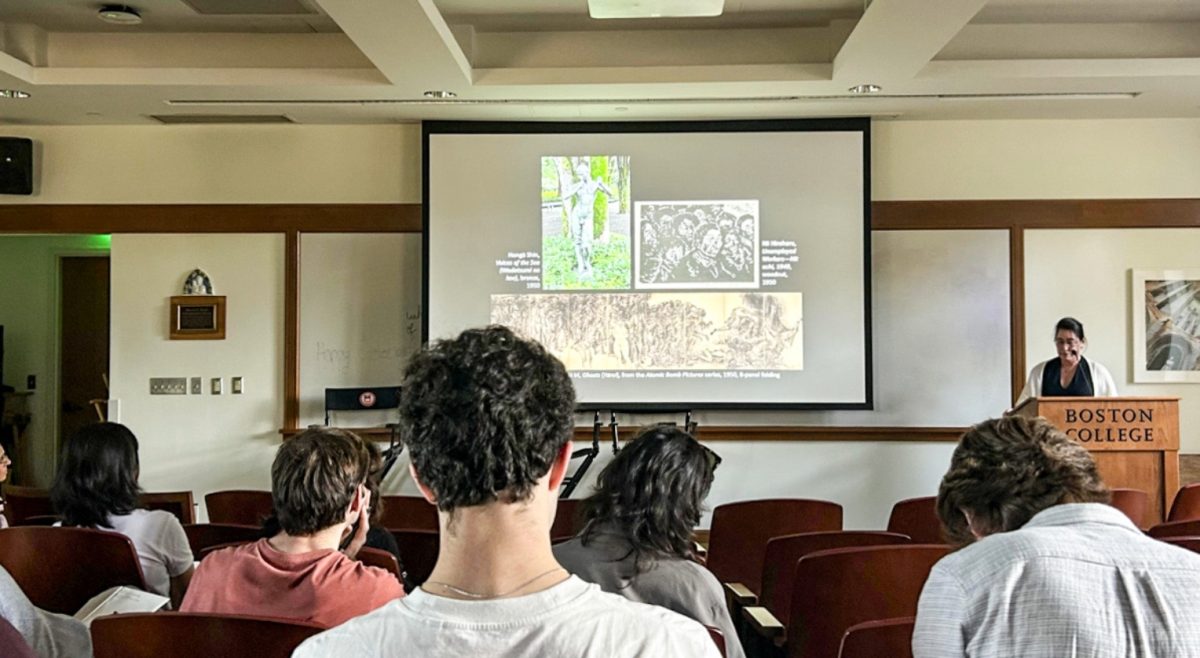

Rikers: An American Prison, which was screened at Stokes Hall last Monday, bridges the mass public to those individuals who have been forced down into the lowest tier of society. Followed by a discussion between two guest speakers who talked of their time as inmates, the evening was one of solemn introspection, and a look beyond the knee-jerk reactions of sympathy and outrage that characterize our usual confrontations with injustice.

Rikers does not portray its subjects as victims, nor as crusaders in a triumphant moral conflict. The human rights abuses we glean so vividly are illustrated through spoken stories of quiet despair punctuated by damaging instances of violence. Occasionally, surveillance footage of the jail will pronounce a reoccurring theme, or provide concrete insight into the speaker’s environment (such as cells and hallways, dotted with the ghostly blurs of inmates rendered in bleak monochrome). The rest is left to the speakers, whose natural coordination of events and their details, guided by an emotional conflict that is real on a level most films can only reach for, impress us with the reality of a lifetime of suffering that hits us with a single, poignant expression.

As with any system of human-rights abuses, life at Rikers is structured by a highly-organized hierarchy of violence to which newcomers must either adapt or submit to, often with grave consequences. As Ralph Nunez describes it, power lies in the hands of two leaders at the top of a ladder of control and command. Their influence diffuses through a task-force, a dayroll, others who have “earned the respect” of the leaders, and to a bottom caste-group labeled the “dayroom dummies.” These are usually young men assigned the duty of cleaning the piss, blood, and sperm out of the other men’s underwear.

Correctional officers, many of whom are from the same background as the inmates they’re guarding, often assist in establishing fights between prisoners and maintaining the order imposed by the gang-leaders. Solitary confinement is their ultimate instrument of punishment. “Everybody’s screaming and it just sounds like a madhouse,” ex-detainee Raymond Yu says. Stripped of all social contact, one starts counting cracks in the wall, playing with feces, and befriending rats and cockroaches. Commenting on his experience, Marcell Neal says, “I started to feel like an animal.”

Though socioeconomically disadvantaged African Americans from the New York area appears to be the primary demographic at Rikers, the system does not discriminate based on an inmate’s circumstances— regardless of race or background, all seem subjugated to the same environmental stresses. Such is evidenced in the case of Kathy Morse, a middle-aged mother from New Jersey who, after embezzling from her law-firm, was sent to Rikers where she experienced abuse. Though their stories are replete with strife and sadness, horror and devastation, we find in ourselves an anger that the speakers do not demonstrate. For them, it seems not a matter of retaliation or sympathy, but of an endurance which their circumstances have pronounced more fervently.

The evening’s speakers, Tom Lynes and Joli Sparkman, related these universal experiences shared between inmates through a voice and narration exclusively theirs.

“Prison is a state of mind,” Lynes said, who had gone in and out of various juvenile detention centers as a child, before finally winding up in Farmington Correctional Facility, where heroin, sexual abuse, and gang-related violence was a part of the community’s very social fabric.

For Lynes, it was just like home. Twice incarcerated, once for robbery and another time for murder, his story was difficult to digest—the audience simultaneously felt empathy, disgust, hope, and then acceptance, of the brute difficulties with which his story is weaved.

Sparkman’s prose-poem, which focused on her failed suicide attempt while in prison, highlighted the tragic irony of her situation, wherein she was forced to pay for the bedsheet she had used to hang herself. If anything is to be gained from narrations of both the night’s guests and those depicted in Rikers, it is that we must suspend our preconceptions of good and evil in order to appreciate the weight of life that’s burdened certain individuals.

Featured Image By Public Square Media

Kathy Morse • Oct 30, 2017 at 9:25 pm

Thank you for allowing myself and the other participants in Rikers to tell our stories. For me it was not only part of the healing process but also to raise awareness that incarceration affects all communities. Be it a family member, a neighbor, a friend, a co-worker it is gradually encroaching on all communities and it is definitely a conversation we all need to have.