When author Bridgett M. Davis’ son asked her what kind of person his grandmother was, words initially failed her—so she immediately set off to write her mother’s story. Unwilling to leave whether the world would know the extraordinary woman her mother was up to chance, Davis recorded memories of her mother and her childhood in Detroit in her memoir, The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers.

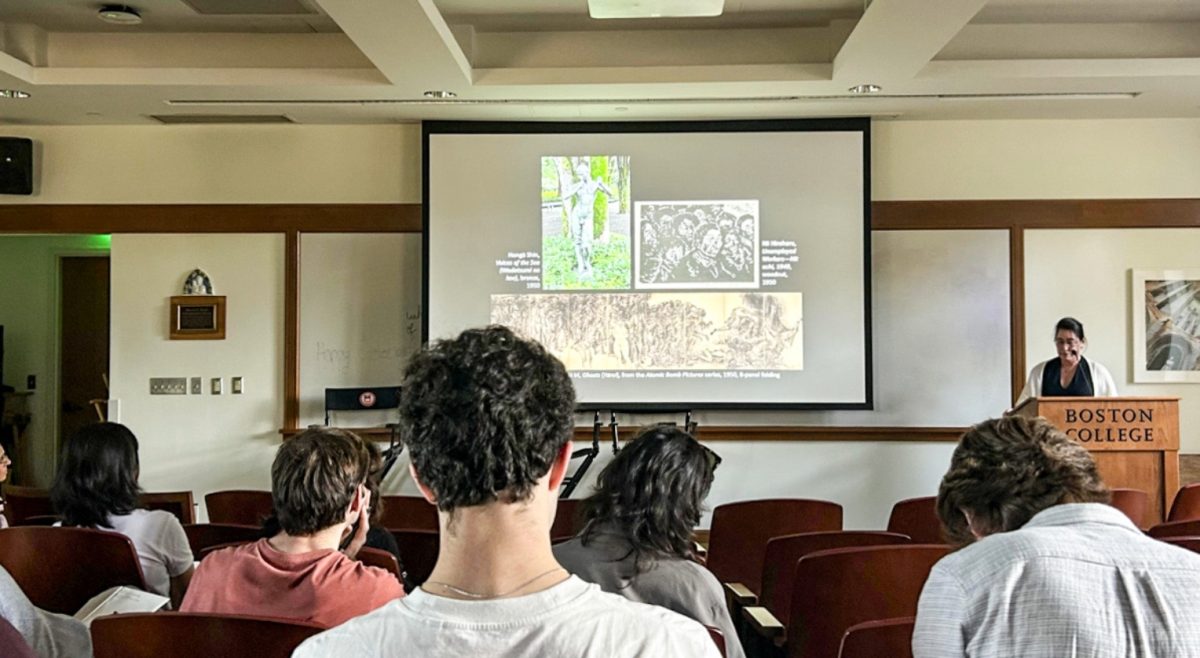

During October 21’s Lowell Humanities Series lecture, moderated by English professor and journalism program director Angela Ards, the author discussed how she created the memoir, which was published in January of 2019, and the essential work the book does by sharing the story of a Black middle-class woman’s struggles and triumphs in Detroit.

Davis said the admiration she always felt toward her mother, Fannie, fueled her as she wrote about her life. Fannie Davis ran a numbers business out of their family home. Davis explained the numbers game referred to an illegal lottery, which can be traced back to the beginnings of colonial America. This lottery provided Black people with an opportunity to start their own businesses, as they were often excluded from the mainstream economy.

Growing up, Davis constantly heard her mother on the phone, collecting bets and growing her business—traits Davis admired as she noticed how Fannie provided her and her siblings with all they needed.

“She was the kind of mother that her own daughter would want to someday write a book about,” Davis said.

Moving to Detroit during the 1950s and 1960s framed Fannie Davis’ experiences. Attempting to escape the racism that was rampant in Tennessee during the years of the Jim Crow laws, Fannie Davis found herself encountering similar incidents in Detroit. The city’s racist policies left Fannie with only tiring service jobs and meager pay. Davis emphasized that her mother’s eventual success at her lottery business is one of many stories of Black people creating their own paths.

“My mother, Fannie, figured out how to do something that Black people have had to do for decades, if not centuries, in this country,” Davis said, “She made a way out of no way.”

As her mother’s business grew, Davis remembered the pride her mother must have felt by providing high-quality education and beautiful clothes for her children. Quoting from her book, Davis recalled the bright yellow shoes her mother bought for her and the books that Fannie filled her shelves with.

Davis portrayed her mother as a complex female character—someone who enjoyed treating herself to expensive garments but always helped other people in her community. Fannie also taught her daughter how to handle the unavoidable racism in the world, and how to demand respect from others.

Davis said her mother’s motto was “You’re as good as anyone, but better than no one.”

Ards joined the conversation by asking what compelled Davis to tell her mother’s story. Ards emphasized the rarity and importance of a character like Fannie, a successful and complex Black woman, in literature. In response to Ards, Davis shared that she no longer wanted to keep her mother’s life a secret, as she had done so for many years in order to avoid revealing the illicit nature of her mother’s work. She decided to celebrate her mother’s life and enduring legacy through her writing.

Davis began her career as a journalist, but she has expanded her craft over the years. Her many titles include novelist, essayist, teacher, filmmaker, and memoirist. When writing her book, her journalistic instincts drove her to relentlessly research the culture in Detroit, she said. She interviewed many people and dug through archival materials to learn about the illegal lottery in the city and her mother’s role as one of the few women in the numbers business.

“I don’t see any separation between those journalistic skills and my quest to be a writer,” Davis said about the intersection of the disciplines.

Ards brought attention to how Davis illustrated middle-class Black people in Detroit throughout the memoir. The author confirmed she wanted to celebrate this thriving population of Black people in the city that she grew up around that were rarely portrayed in literature. Davis’ memoir adds to the growing number of stories of people of color that are now being published.

“There are so many stories out there that are waiting to be told,” Davis said.