Ivor Bell, a former Irish Republican Army (IRA) leader, was aquitted last week of the 1972 kidnapping and murder of Jean McConville, for which he was accused at least in part due to tapes recorded as part of a research project at Boston College.

In a statement to The Heights, former IRA member Anthony McIntyre noted his satisfaction with the court’s ruling. McIntyre, who was imprisoned for 18 years on murder charges before earning a Ph.D. in history, was responsible for conducting many of the Belfast Project interviews with former republicans.

“I welcome the acquittal of Ivor Bell and the ruling by the court that the tapes were inadmissible,” McIntyre said to The Heights in a Twitter direct message. “The Belfast Project Oral History was an important and valuable archive that would have greatly contributed to society’s understanding of conflict and the recent past in Northern Ireland. The handover of the tapes was something I vehemently protested. Boston College could have, and should have, done far more to protect this research and the collapse of the Bell case bears this out.”

The recordings, part of the Belfast Project but more commonly known as “the Boston Tapes,” were conducted by BC faculty who were documenting the Troubles, a contentious period of time in Ireland’s history which saw numerous terrorist attacks and widespread violence between Irish nationalists and British loyalists.

The conflict, which stretched from the late 1960s to 1998, centered on the status of Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom, with Irish nationalists, known as republicans, fighting British police and non-state loyalist paramilitary organizations.

The IRA and various other republican sects fought for Irish unification, while various loyalist militias fought for Northern Ireland to remain in the United Kingdom, along with British police forces.

The Belfast Project launched in 2001, three years after the Good Friday Agreement—an international peace treaty that effectively ended the Troubles. Researchers interviewed numerous former paramilitaries regarding their involvement in the conflict. The interviewees were promised before the tapes that their recordings would remain secret until their death, so that they would not face legal trouble for their testimony.

Following an interview Dolours Price gave in 2010—during which she talked about her involvement in the Belfast Project and indicated that she drove McConville to the spot where she would be shot—the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) launched a legal battle for BC to release all relevant interviews.

Bell was accused of being “Interviewee Z,” who admitted on the tapes to involvement in the decision to have McConville, who the republicans believed was an informant for the loyalists, executed. His defense to the accusations rested in part on the fact that it could not be proven that he was Interviewee Z, and therefore the tapes could not be used as evidence against him.

The British government then subpoenaed the tapes, and they were turned over to British courts after a 2011 order by the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts directing BC to do so. The University was ordered to release the interviews of Price and Brendan Hughes, both former IRA members. BC then filed to close the case in January of 2013.

In May of 2013, a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit stated that the district court had “abused its discretion” in its initial subpoenas and that just 11 of the 85 interviews originally ordered to be released were relevant to the McConville investigation.

The PSNI announced in March of 2014 that it seeked to question McIntyre regarding the released tapes, specifically in reference to the alleged role of Gerry Adams, the former leader of the republican political party Sinn Féin, in the kidnapping and killing of McConville. He was arrested in the spring of 2015 and was subsequently released that September.

The University announced in May of 2014 that, upon request, it will return all interviews to the relevant interviewees.

Hughes said in his interview that he helped orchestrate Bloody Friday, in which the IRA detonated over 20 bombs in the span of about 80 minutes, mostly targeting infrastructure and transit. Nine people died and 130 were injured. Hughes also acknowledged in the tapes his involvement in the McConville shooting.

BC has faced heavy criticism for what is seen as a major violation of academic integrity—misleading research subjects about the risks they were assuming when engaging in the project.

“We knew that from the first subpoena issued,” wrote Carrie Twomey, who frequently writes about the tapes on her blog The Pensive Quill and is married to McIntyre, in response to the inadmissibility of the tapes. “Boston College had a duty to fight much harder against the subpoenas than what they did for precisely this reason: They were not evidence, they would never stand up in court, the pursuit of them was an abuse of process and an egregious abuse of the [US-UK treaty on mutual legal assistance] … Shame on them for not protecting their researchers, their research, and, most importantly, their research participants.”

In 2018, Bell was deemed unfit to stand trial and excused from the hearings, after which a “trial of the facts” began in an attempt to parse out what actually happened. Last week’s ruling found that it could not be proven that he had involvement in the disappearance of McConville.

It is important to note that the factual accuracy of the tapes was disputed in court, which is another aspect of why the tapes were not admissible as evidence. As someone who was also involved in the conflict, McIntyre’s line of questioning provides significant evidentiary problems, and memories tend to be highly subjective. Twomey has also argued that oral histories cannot be considered sworn testimonies or confessions.

“He might have felt liberated and free to tell the truth and to leave as his legacy his version of the Troubles,” wrote Justice John O’Hara in the decision. “The difficulty is that he might also have felt free to settle scores with his former colleagues who he believed had betrayed their cause. He may have felt free to lie, to distort, to exaggerate, to blame and to mislead.”

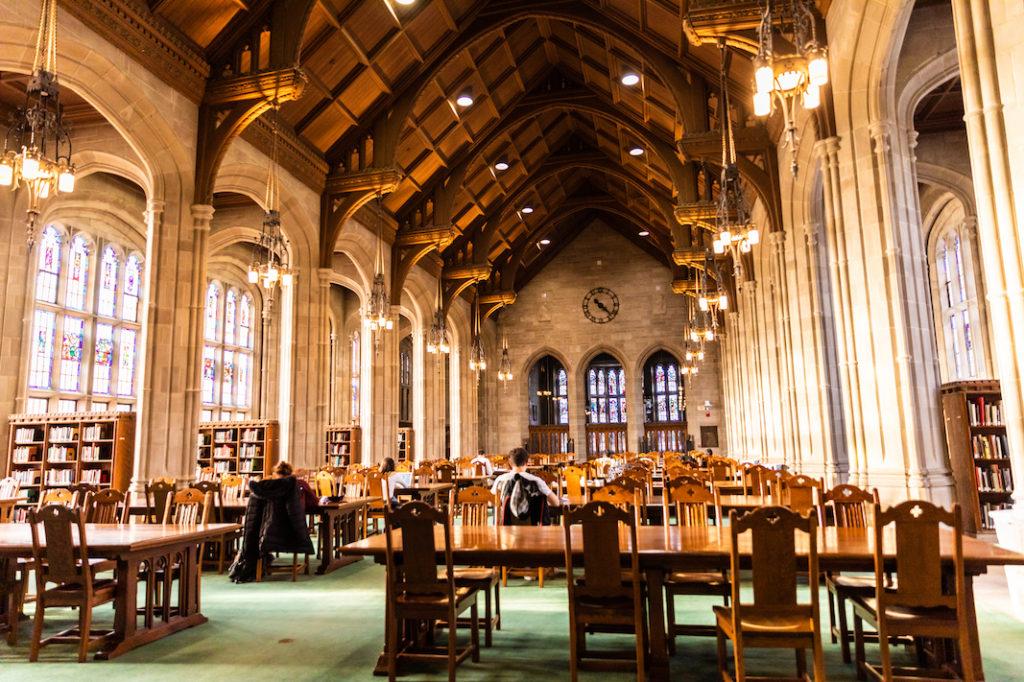

Featured Image by Jess Rivilis/Heights Staff