Something had caught five-year-old Makenna Newkirk’s eye as she took off her newly-worn skates at an ice rink in Scottsdale, Ariz. and prepared to leave from her first class, earlier in the day. On the ice where she had just slipped and slid, struggling to keep her small frame balanced, there was now a collection of boys skating effortlessly, moving around the ice and passing a hockey puck back and forth. It was mesmerizing.

“I wanna do that,” she said. Though she’d only just before taken her first steps on ice, she was ready for a bigger challenge.

Her father, assuming that she would not remember by the time she got home, held off on calling the league. But then came the questions.

“Have you called ’em yet?”

It was a tall order, considering Newkirk’s geographic positioning in the hockey world couldn’t have been farther off. Living in Scottsdale, when she first asked her dad to play, there were minimal programs for young boys and girls interested in hockey. Newkirk’s parents were ill-equipped to deal with a hockey-playing daughter. With her mother from Missouri and her father from California, neither had grown up knowing the sport.

“I didn’t really believe people put blades on the bottom of their shoes and skate on ice,” her father, Greg Newkirk, said.

So after days of pestering, he broke down and called. And Boston College women’s hockey is glad he did, since the now-freshman is making waves on the team. She has notched 18 goals and 21 assists this season, and is second only to Minnesota’s Sarah Potomak on the freshman point-scoring list.

***

Like most sports, co-ed hockey eventually gives way to single-sex teams once kids become older. She worked her way up the ladder, landing on rosters throughout the Southwest. Eventually, Newkirk’s talent had expanded past what the region could offer her, even when tournaments took place in Michigan and Illinois, closer to the hotbed of hockey.

When she tried to play an age division up, a team in Colorado said that she had to be in the top 3 percent of 28 forwards who tried out. As No. 5, she didn’t make the cut. Frustrated with the dead ends the leagues at home gave her, she handed her father a slip of paper with the name and number of a hockey coach for Team Pittsburgh, a travel team based 2,047 miles away from home that featured fellow future Eagle Gabri Switaj. It was a part of USA Hockey, a league for national youth play. After flying out to meet the coach and skating for him, she landed a spot on the team. Eventually, in 2013, Newkirk led the team to the championships, only to lose by one goal to a team that had future teammate Kenzie Kent on the roster.

Instead of moving to somewhere closer when she got on the team, she spent the first two years traveling back and forth between home and hockey, flying into Pennsylvania at least once a month for games. With the stress of travel and only few absences allowed a semester, Newkirk switched to online schooling. Six months later, she decided that the best way to be a part of her team in Pittsburgh was to be nearby. She approached her parents with the idea of going to prep school.

When her father questioned the financial repercussions of attending a high-end high school, Newkirk, knowing that the benefit of a prep school could earn her a college athletic scholarship, offered a short response:

“Pay now or pay later.”

After a few tours, she decided to fully uproot her life in Scottsdale for the Pomfret School, a boarding school in Connecticut. There, she engaged in a full three seasons of school sports (soccer, softball, and, of course, hockey) on top of her travel team commitments. She flourished on the field and rink and off, landing on the honor roll at the highly touted institution.

***

One of the earlier cuts included Harvard, the best-known school in the Ivy League and the home of one of the most successful women’s hockey programs in the country. The Crimson is led by its highly successful head coach, Katey Stone, who is the second all-time winningest coach in women’s hockey history. Stone has led the best players across the nation to the Olympics as the head coach for Team USA at Sochi in 2012. There had to be a good reason to pass up an opportunity to grow under Stone’s tutelage.

But Newkirk, seemingly drawn to the place where she had watched national championships and worked in development camps, chose BC, a team on the up-and-up. In the 2014-15 season, the Eagles won all but five games, losing three integral matches—the Beanpot final, the Hockey East final, and the NCAA finals—and tying in two regular-season games. A stunning 34-3-2 record, but three losses. It may not seem like a program that successful would need such a talented player to contribute so quickly. But after coming so close to etching their names among the all-time legends in the sport, BC and head coach Katie Crowley needed that “missing piece.”

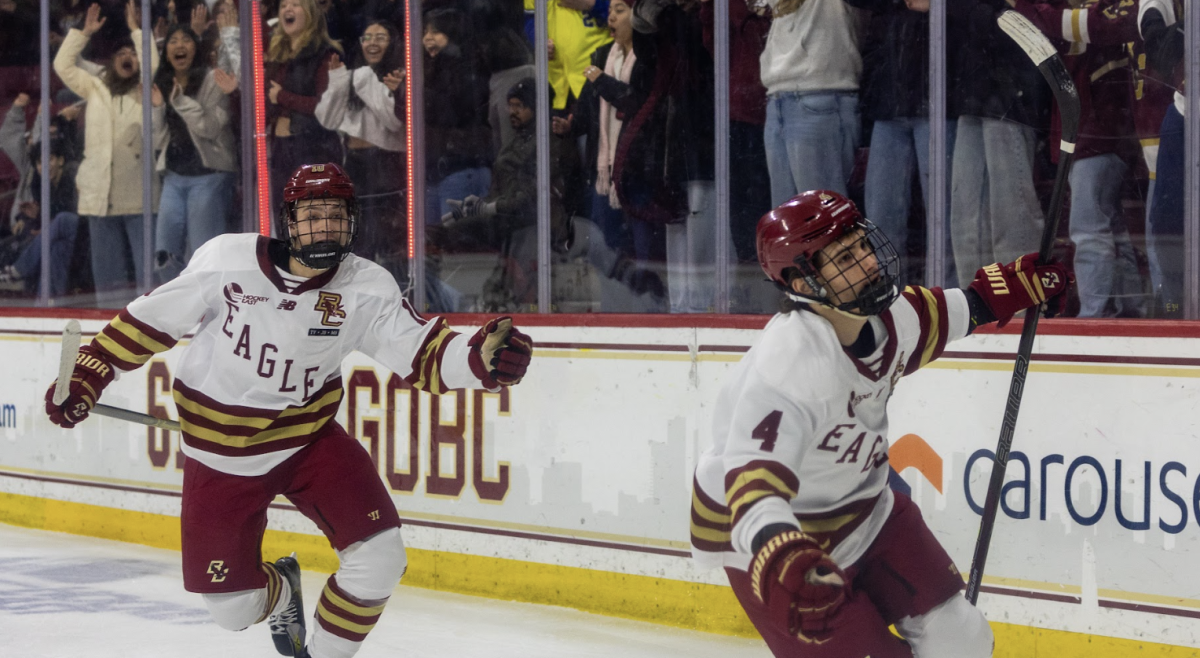

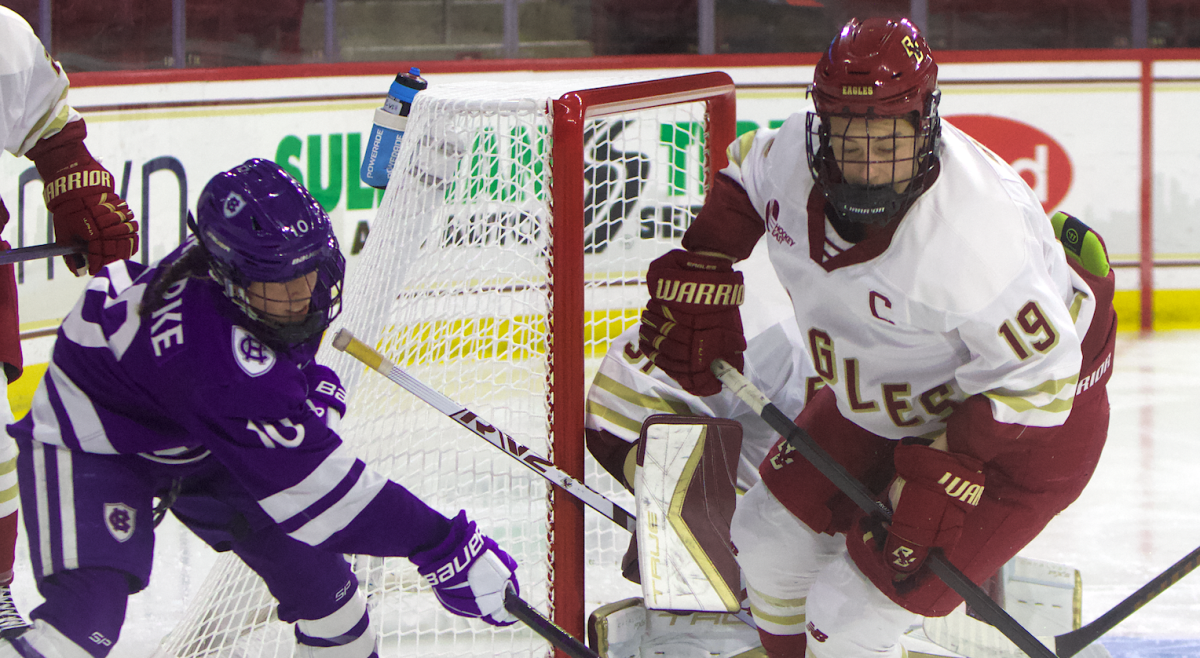

She has played in every single game this season. She has played on the first line with BC greats Haley Skarupa and Alex Carpenter, the latter of whom is possibly the best woman who has ever played the game. When faced with the Beanpot final against Northeastern, Newkirk hit a stride and quieted all doubts of another tournament loss. She scored a goal sandwiched between two assists. Newkirk took a powerful shot on goalie Brittany Bugalski that initially looked like a deflection, but actually slid past her.

After the trophy was claimed in a dazzling 7-0 victory, Newkirk reflected on the game with her father. “I said, ‘Were you nervous?’ and she said, ‘Not really. We knew what we needed to do,’” Greg said.

What sets Newkirk apart from her peers is her ability to read the ice and make plays happen. During the Northeastern match right after the Eagles’ victory against the team in the Beanpot, Newkirk stripped the puck by the Huskies’ goal and passed it behind her, setting it up for a teammate right in front of the goal, though no one was there. In the same game, she took control of the puck, slowed down, and shot high as a Husky defenseman was coming toward her. She sent the puck flying past Bugalski’s left shoulder. Less than two minutes later, she waited farther out from the goal to get a pass from Carpenter. The second the puck hit her stick, it went hurtling past Bugalski again. As a player with one of the highest numbers of assists—she’s fourth on the team, behind captains Carpenter and Skarupa, and sophomore defenseman Megan Keller—Newkirk is all about getting the puck in the net, no matter who scores it.

***

By her age, Newkirk should be a junior, and many of her friends will exit the college scene before her. Instead of pining for adult life in the “real world,” Newkirk is content with the way things are going now.

“I’ve asked her every once in a while about how she’s going to be in school for longer and that stuff, and her response is, ‘Yeah, but I have another year of hockey,’” K.C. McGinley, her close friend and a club hockey player at Arizona State, said.

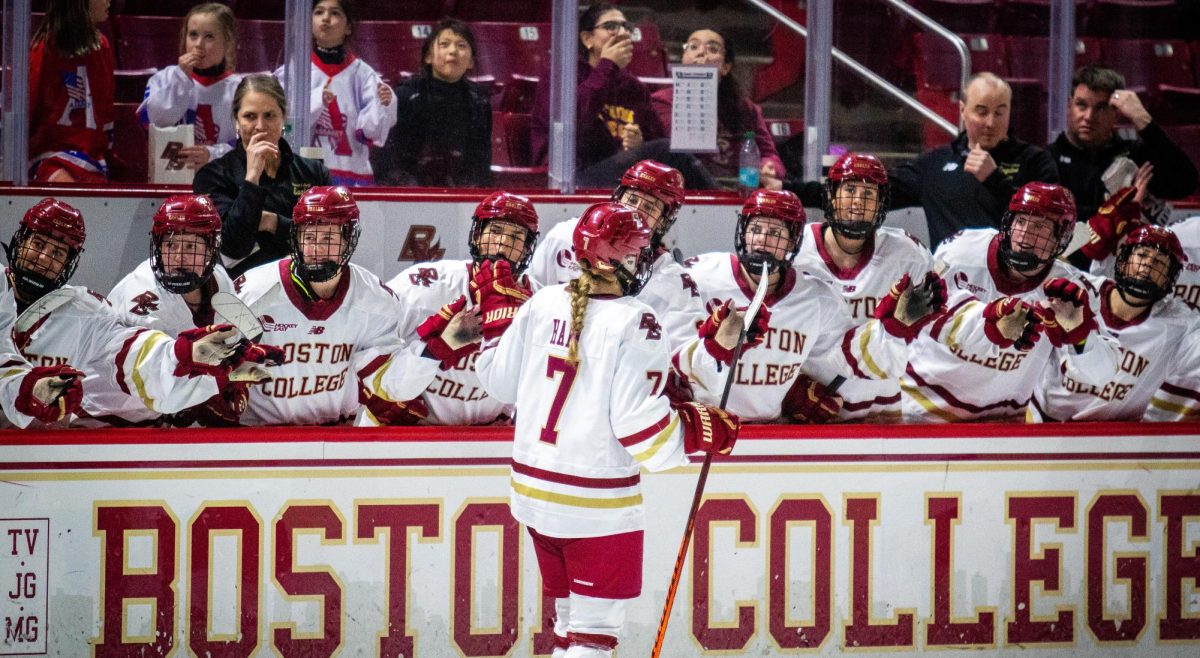

For now, Newkirk is taking it all in. She loves to recall the first time she stood shoulder to shoulder with her teammates on the blue line at Kelley Rink, waiting for Andy Jick to announce the starting lineups, eager to face a women’s hockey powerhouse, the University of Minnesota Duluth. The five skated up to the other blue line, and then the opening notes of the pre-recorded, instrumental version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” blared through the stadium’s speakers.

“I didn’t know where to put my helmet or what hand to hold it in,” Newkirk said. “[BC defenseman Toni Ann Miano] was laughing at me.”

But amid the swell of the music, it finally hit Newkirk that she was here, playing on one of the best teams in college women’s hockey—no longer one of two girls in a co-ed league.

Newkirk was an Eagle now, and she would waste no time proving her worth on the team.

The incessant questions of the five-year-old girl from Arizona finally paid off.

Featured Image by John Quackenbos / BC Athletics