Casper Augustus Ferguson, the first Black student at Boston College, graduated from BC in 1937. In the 10 years after Ferguson’s graduation, only six Black students earned a BC diploma. Ferguson was a trailblazer, but his presence on campus was only the beginning of a nearly century-long—and still ongoing—fight for full integration and racial equality at BC. Since the 1930s, Black athletes, coaches, and athletic administrators have frequently led the fight against racial discrimination on the Heights.

In the following 60 years after receiving his degree, Ferguson returned to the Heights only twice: once to see Ernie Davis, a Syracuse player who became the first Black player to win the Heisman Trophy, and once for an AHANA Alumni Association dinner in his honor in the ’90s.

One of the six Black students who succeeded Ferguson was Lou Montgomery, BC ’41, the first Black athlete at BC. Montgomery arrived just a semester after Ferguson’s graduation. He was a running back for the football team and one of three Black students in his class. Six times throughout his four years on the Heights, BC barred him from competing against southern schools because of the “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” which competitors who refused to play against Black athletes requested and BC complied with. Three of those games were home games, and two were bowl games.

Heights coverage at the time reported on BC’s treatment of Montgomery but did so without denouncing it. In 1939, The Heights described discrimination against Montogomery as “foolish and time-worn bias.”

In choosing to attend BC, Montgomery turned down an offer from UCLA, where he would have played football with Jackie Robinson, who arrived in Southern California two years after Montgomery first took the field with the Eagles. BC football arguably reached its peak during Montgomery’s time, finishing with a perfect season and a debated national championship during his senior year in 1941. Montgomery, however, was not allowed to play in the Sugar Bowl, as it was against southern opponent Tennessee. Despite the adversity he faced every time he took the field, Montgomery was renowned for his love for football and commitment to the game. In 1997, Montgomery was posthumously inducted into the BC Varsity Club Hall of Fame, and his jersey was retired at Alumni Stadium in 2012.

Montgomery was a trailblazer, but it took decades before other Black student-athletes had a chance to walk in his footsteps. In 1955, there was only one Black player on the Eagles’ football team. Larry Plenty, also a running back, averaged 5.7 yards per carry on 42 attempts during the 1955 season. He also played punter and averaged 28.4 yards per punt. Plenty was a two-sport athlete, and during the 1957 baseball season, he led the team with a .389 batting average.

“[Plenty is] the only member of our team that has lived up to my expectations,” then-head baseball coach Johnny Temple told The Heights after a disappointing 1957 season. “There is nothing at all surprising about Plenty’s fruitful production this season, for he possesses all the necessary requirements demanded of a great athlete: The arm, speed, physique, batting power, and above all, the natural ability.”

The Heights revisited Plenty’s standout 1957 season in a 2002 article entitled “Diversity Finds a Place at BC,” which also featured John Austin, BC ’66.

Twenty-one years after Montgomery’s graduation, Austin arrived at BC in1962 as the Eagles’ first-ever Black basketball player. Austin played on the varsity team for three years and is still one of the greatest players in school history to this day. He still holds program records for career scoring average with 27.1 points per game over three years, season scoring average of 29.2 points per game in 1963-64, and points in a single game with 49 against Georgetown.

Austin’s time as an Eagle began a year after Celtics legend Bob Cousy arrived at BC as the Eagles’ head coach, and the two played a major role in rebuilding BC’s basketball program.

“[Austin] was probably the most skilled player I coached at BC,” Cousy said in an interview, the Heights reported in 2002. “There were a lot of great players, but John had the most skill.”

He graduated as the program’s all-time scoring leader and sits among the top 10 today with 1,845 career points. He was a two-time All-American—BC’s first-ever—and holds the record for the first, second, and third-most points scored in a game.

“If a Boston College basketball fan should happen to miss a game, there are two questions which he will inevitably ask—What was the score? and, How many did John get?” a Heights article from 1966 read.

Austin led BC to two National Invitation Tournaments during his time as an Eagle. As not only the first Black player but also arguably the best guard in program history, Austin paved the way for countless athletes to follow and helped put BC basketball on the map. Austin died in early November of 2020, but his legacy lives on both on the court and in the record books.

It took another seven years after Austin’s graduation for a Black female athlete to make her mark on the athletics program. When Doxie McCoy arrived at BC as a freshman in 1973, the school had been co-ed for just three years, Title IX had been in place for less than a year, and there was no women’s ice hockey team. While there is no official documentation of who the first Black female athlete at BC was, McCoy is a likely candidate.

McCoy was a multi-sport athlete during her time as an Eagle, taking advantage of recent Title IX changes to be a driving force behind the creation of BC’s first women’s ice hockey team and a member of the newly created field hockey team. Longtime great men’s hockey coach John “Snooks” Kelley tapped McCoy to be a founding member of the women’s ice hockey team despite the fact that she didn’t know how to skate.

“When I came to Boston College, I was used to being in the minority,” McCoy said to BCEagles.com. “But by the same token, I was never held back in terms of pursuing the things that I wanted to do. Because I thought, if not me, then who will? I’ve never been afraid to try to break barriers and encourage any student who feels like they can contribute and feel like if they’re the only one then don’t be afraid to be the only one because we need the first only one.”

McCoy’s involvement on campus did not end with athletics. She founded a minority-led newspaper called Collage and was a sports writer for The Heights in keeping with her communication major. As editor-in-chief of Collage, McCoy served as a voice for underrepresented students on campus, at one point calling out the BC administration for removing the Black Talent Program meant to recruit more Black students. McCoy was also involved in protests at BC urging the administration to increase the campus’ minority population.

Almost 50 years later, BC is still making strides toward racial equity. Martin Jarmond’s hiring as athletics director in 2017 was barrier-breaking for a number of reasons. First, Jarmond was the youngest AD in the Power Five. Second, he was BC’s first ever AD of color, and at the time, BC employed no minority head coaches. Jarmond’s time as AD was short—he departed for UCLA in the summer of 2020—but his impact was lasting. He oversaw the transition of power between Steve Addazio and Jeff Hafley at the head of the football program. He also hired women’s soccer head coach Jason Lowe, BC’s only current Black head coach.

From practically his first day on the Heights, Jarmond began to roll out never-before-seen initiatives across the athletics department. From introducing alcoholic beverages in Alumni Stadium to overseeing the massive construction project of the Pete Frates Center on the Brighton Campus, Jarmond was everywhere.

“When you’re in the competitive world of college athletics, it’s never enough,” Jarmond said in a 2018 interview with The Heights. “That doesn’t mean that we’re going to build the Taj Mahal, but we need to put our coaches and our student-athletes in positions where they can be successful.”

Just months after the addition of Jarmond to the athletics administration, BC hired Jocelyn Gates, the highest-ranking Black female in BC Athletics, to assume the role of senior associate athletics director and senior woman administrator. She is also the departmental deputy Title IX coordinator. After just three years on the Heights, Gates was named FBS Administrator of the Year. A former student athlete, having played soccer at Howard University during her undergraduate years, Gates is intentional about advocating for student athletes of color.

“I am here for every student-athlete, there is a special place in my heart for the student-athletes of color,” Gates said in a 2019 interview with CollegeAD.com. “I feel like I need to be a voice for them and young administrators of color. They need to see a face like their own in administration and know they can do it too.”

Jarmond’s arrival at BC came 20 years after BC men’s basketball hired Al Skinner, the only Black head coach of a revenue sport in the school’s history. Before starting at BC, Skinner played a long career in the NBA and had head coaching experience at the University of Rhode Island. Skinner’s first three seasons at BC combined for just 12 wins in the Big East, but he turned his luck around the next year when he led the Eagles to a Big East title–their first regular-season title in 18 years. The 2000-01 Eagles also earned a No. 3 seed in the NCAA tournament, and Skinner was named the NCAA Coach of the Year at the season’s close.

BC men’s basketball appeared in March Madness in six of its next nine seasons with Skinner at the helm. His 2005-06 team made it the farthest BC has ever gone in the NCAA playoffs, as its season ended in the Sweet 16. Skinner was fired in 2010 after his second season below .500. He is still the winningest coach in BC men’s basketball program history, and his firing remains controversial.

BC, along with other institutions, has also made progress in bringing change to areas of college sports that have remained largely exclusive to people of color. On Feb. 11, NCAA Division I Hockey announced the formation of a College Hockey for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiative. A group of 27 people, including student-athletes,coaches, and administrators from all 11 Division I hockey conferences, leads the initiative..

BC defenseman Marshall Warren is one of the five members of the group from the Hockey East. Warren, who is the only Black member of the BC program and one of just a handful of Black players across all of Division I, posted on social media that he hopes the initiative will “create change within hockey as a whole.”

The announcement of the new initiative was the latest step in a year marked by the intersection of race, sports, and activism. In August, BC football opted to cancel practice in response to the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wis. The decision came on the heels of a number of other boycotts by college football, basketball, and baseball teams across the nation. Instead of practicing, the Eagles met as a team and discussed issues of racial injustice.

“We decided not to practice today,” BC head coach Jeff Hafley said in August. “A bunch of things have obviously gone on in our country, and with the recent events that happened, we felt as a staff and as a team that it was best not to practice.”

While BC has come a long way since Ferguson’s first year on campus, there is still much room left for progress. Only one revenue sport at BC has ever been led by a Black head coach, other than Rich Gunnell’s interim position last season. The name of BC’s Yawkey Center, the hub for BC football staff and players, as well as the Office of Learning Resources for Student-Athletes, recently came under fire. The building was named for Thomas “Tom” Yawkey, long-time owner of the Red Sox, who has faced criticisms recently because the Red Sox were the last Major League Baseball team to integrate Black players. The Red Sox opted to rename Yawkey Way, the street outside of Fenway Park, to Jersey Street in 2018. BC decided to retain the Yawkey name on the building in 2018, citing requirements in an agreement with the Yawkey Foundation, one of the key benefactors in the building’s construction.

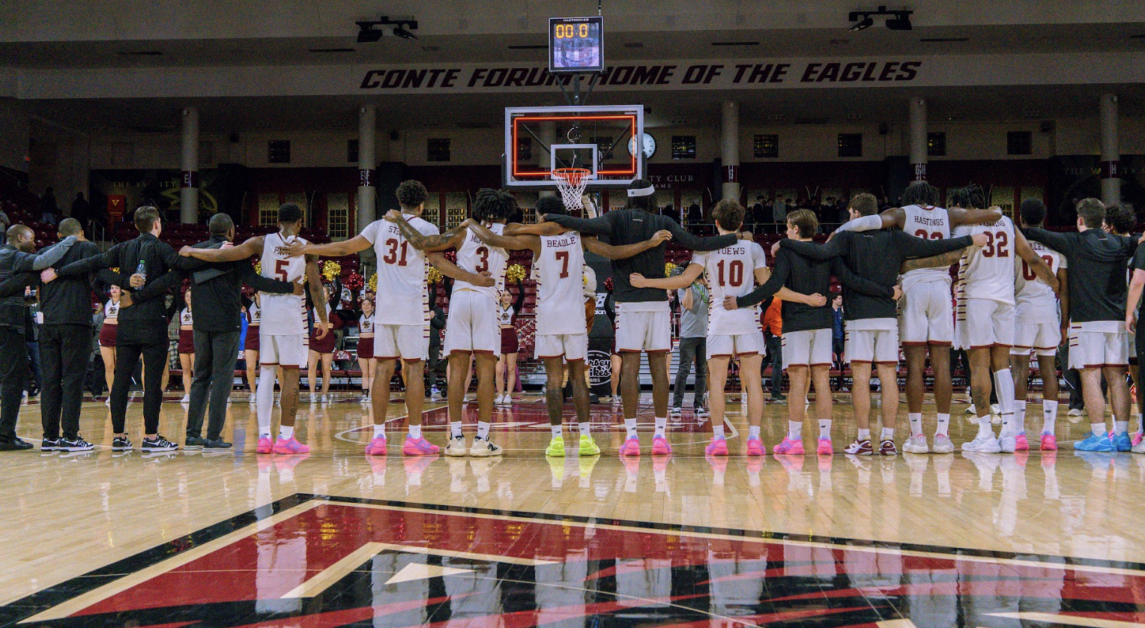

To continue progressing forward in racial equality within athletics, BC founded the Eagles for Equality initiative. The initiative includes a 14-person committee of student-athletes and aims to educate the BC athletic community and build a “more inclusive environment for all marginalized student-athletes and to enhance their experience at the Heights.”

“It is clear that the voices of student-athletes need to be heard now, more than ever, especially on critical topics such as inclusion, social justice and equality,” Athletics Director Pat Kraft said on BCEagles.com. “The creation of this outstanding committee will provide us all with guidance to create necessary and long-lasting change.”

Featured Image Courtesy of BC Athletics

Other Images Courtesy of BC Athletics, by Ikram Ali / Heights Editor, by Chitose Suzuki / Associated Press