The Holocaust is most well known for the systematic persecution of Jews, gypsies, and other minorities in Germany, while the legal attacks of Nazi Law often go undiscussed.

Legally Blind, a two-day conference sponsored by several groups on campus, including the Winston Center for Leadership and Ethics and the Jewish Studies program, brought together five panels to discuss the effects that the Nazi Laws had on civil laws, race, and religion within Germany and Western Europe.

The conference examined three areas of life that were impacted by the promulgation of Nazi Laws. Tuesday’s panels focused on the impacts the Nuremberg Laws had on Jews in both Germany and France.

The panels on Wednesday examined the effect Nazi Laws had on medical and religious policies within the Third Reich, and took a closer look at the Nuremberg trials that convicted many prominent leaders within Nazi Germany for war crimes committed beginning in 1933.

The event also featured a concert of Jewish music Tuesday night with performances by vocalist Monika Krajewska and pianist Natasha Ulyanovsky.

“Once the law was kicked out, the new totalitarian system moved into place,” said John Michalczyk, the director of film studies and co-director of Jewish studies at Boston College. “This conference is starting at that point and ending with the Nuremberg Trials where everything that happened during the 12-year period was subject to the law.”

In March 1933, a law was enacted that revoked the access to the court system of Jewish judges, prosecutors, and attorneys. Scholars often raise the question of why non-Jewish lawyers did nothing about this legal injustice, yet there is no real answer.

All that can be said is that the exclusion of Jewish lawyers and judges allowed the Third Reich to receive judicial rulings in accordance to Hitler’s ideologies, Michalczyk said. Always under the pretense of protecting the state, the Third Reich implemented legislation that consolidated Hitler’s powers, legislation that was always found legally acceptable by the courts.

“Hitler and the Third Reich basically abandoned constitutional law from the earlier Weimar Republic, and moved in measures that basically were emergency measures that lasted forever just about, and those are the ones that brought a control of the population,” Michalczyk said.

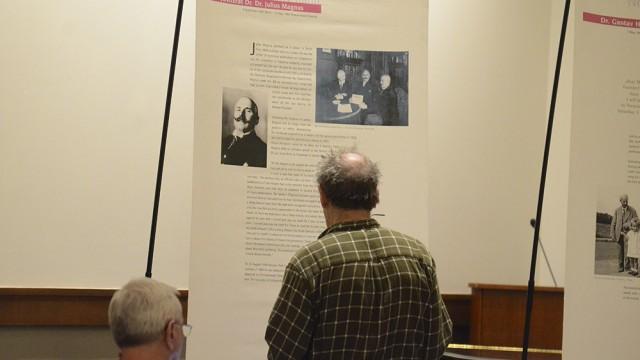

A visually prominent portion of the conference was a series of posters displaying some of the first Jewish lawyers and judges excluded from the legal system. The display, Lawyers Without Rights, was a joint creation between the American Bar Association and the German Federal Bar, and has been shown in over 70 cities worldwide and 12 cities in the U.S. The panels give a detailed glimpse into the life of each law official, emphasizing their successes before the laws passed in 1933, and the struggles they faced throughout the years that Hitler held power.

Michalczyk is also using the conference to bring together scholars from the U.S., Israel, France, and Germany to help write a book and produce a documentary centered on the topics discussed at the conference. Each expert will be have a 30-minute interview that will be cut into the documentary and they will each be asked to write a portion of the book which will then be edited by Michalczyk and Rev. Ray Helmick, S.J.

The conference did not focus solely on the historical aspects of the Hitler’s totalitarian rule. Though the U.S. might condemn Hitler’s regime, it is not completely without fault, according to Michalczyk. After Sept. 11 there was a rise of what some called “new anti-semitism,” but instead of the persecution of Jews, they believe the focus was pushed to Arabs and Muslims.

“Our hands are not clear either because the CIA has used torture, and did not respect the dignity and the personhood of an individual,” Michalczyk said.

BC has a reputation as an institution conscious of social justice, which is why Michalczyk pushed to organize the conference.

In order to properly educate the public about the ethical consequences of racial or social persecution and prevent its occurrence in the future, it’s necessary to examine the past and apply the findings to the present, Michalczyk said.

Featured Image by Arthur Bailin / Heights Editor