“I was like, ‘S—t, I might just be a big stiff for the rest of my life.’”

As far as the rickety, treacherous world of hand-shot high school sports footage goes, this YouTube clip is of a remarkably rare, wonderful breed. A bit shaky and featuring some cinematically uncouth camera zooms and baffling special effects—but coming in pristinely at 720p—the video features footage from Dec. 27, 2008. Bridgewater Raynham is putting a beat-down on North Quincy. Wearing No. 55, looming what seems like 55 feet above everyone else on the court, 16-year-old Dennis Clifford is impossible to miss.

Getting low on defense, Clifford’s arms are swinging out wide. He’s stutter stepping with a lightning-quick ease, and side-shuffling nimbly with his man. A forced bounce pass leads to a turnover and a fast break. Clifford sprints down the court alongside the interceptor with a lanky dexterity. His teammate muffs the layup, but Clifford is there. Slamming the ball home and taking the foul, the big man leaves the overmatched defender defeated on the floor.

The crowd goes freakin’ nuts—one man wearing a Michael Vick Falcons jersey simply stands there stunned, covering his mouth—and once his teammates finish mobbing him, Clifford heads to the line. From breaking out of the paint to burying the rebound, Clifford’s entire sequence lasts five seconds.

“Did you get that on video?” someone marvels.

Six years is a long time. It’s enough time to finish growing and round out at a diminutive tree-sized 7-foot-1. It’s enough time to, as a freshman on the Boston College men’s basketball team, play in 31 games, start in 25, and—by averaging nine points and five rebounds a game—emerge as a cornerstone for the future. It’s enough time to be named a sophomore captain of a program apparently on the rise, to become the most strikingly visible member of a young, talented team.

It’s also enough time to watch helplessly, and endure miserably, as everything spirals into a frustrating black hole of inescapable pain.

“I loved moving around, and that was kind of my identity on the court,” Clifford said. “And then, sophomore year, I was like, ‘S—t, I might just be a big stiff for the rest of my life.’”

Leaning forward on a metal folding chair in Power Gym, Clifford cools down after an October practice. For the first time since his sophomore preseason, Clifford’s playing without pain and going 100 percent. BC head coach Jim Christian and his staff are keeping a cautious eye on the center—making sure wear and tear and overuse don’t spark an injury relapse—but right now, Clifford hasn’t felt this healthy in ages.

“Phew, that was a long time ago, that was probably freshman year,” Clifford said. “I’m even feeling better now because I’ve gotten bigger and stronger. I’ve had the chance to grow into my body. Now I’m feeling even better on the court where guys aren’t pushing me around as much. You know what I mean? I’m starting to do what I’m able to do.”

Clifford seems fully recovered—mentally and physically—from an injury ordeal that stretched over two harrowing years and forced him to wonder if he’d ever make a full recovery. It led to a sophomore season spent playing in pain, knee surgery, a medical redshirt as a junior, and the disappointment of an uncomprehending fan base. It all started with a dunk.

Two years ago, Clifford went up for a dunk in a preseason practice and tweaked his left knee coming down. He limped off the court, knowing something was wrong. Clifford played on and tried to rehab it, but the injury worsened. MRIs indicated some mild irritation behind his patella, but other than that, they came up clean. As a former high school soccer midfielder and defender, Clifford built his game on the court around his speed and quickness—he wasn’t a lurching mountain of a body, he was a big guy who could move. But as the injury persisted, all of a sudden he physically couldn’t move the way he needed to.

Then, everything got worse. Against Penn State, Clifford rolled his right ankle. He had been overcompensating with the right side of his body to carry the left, and suddenly, there was nowhere else to go. He missed the subsequent three games but continued to play in front of confused fans, never scoring double-digits, his legs damaged and always in pain.

“If [Olivier Hanlan] drove a lane and dished it off to me, I couldn’t even friggin’ do anything with the ball,” Clifford said. “There was a point where [former head coach Steve Donahue] was like—I was just in such bad shape—that Coach was just like, Yeah, stay on the opposite side of the ball. I was basically just in there to be a big body on defense.

“Part of me was like, ‘I’m just gonna have to stick with it and change my game,’ and the other part was like, ‘Jeez, this sucks.'”

At the start of his junior year, Clifford, his parents, and Lyle Micheli of Boston Children’s Hospital decided he should undergo surgery. The procedure cleaned up some debris in his knee, but the pain persisted and he was unable to get back as quickly as he’d hoped. BC’s doctors diagnosed him with bilateral chondromalacia and said there was a chance he was always going to feel some pain or discomfort. The junior kept trying to come back, but the pain would always hobble his efforts.

“There would be days I felt better, and I was like, ‘Oh s—t, I might be able to play again,’ and then the next day I’d be back to square one again,” Clifford said. “If you sit out for a whole year straight, going back to 100 percent, you’re not going to be ready for anything.”

Clifford missed the first 14 games of last season, recording 12 minutes against Clemson and 21 versus Virginia Tech. Growing increasingly frustrated with the situation and BC’s push to have him play through what it considered a chronic condition, he finally decided to take a medical redshirt before the Syracuse game on Jan. 13.

“I didn’t know any better sophomore year so I kind of just played through that—that’s what they were telling me,” Clifford said. “But my junior year, I was like ‘Listen, I kind of want to give this a try.’ So I wasn’t in shape, I wasn’t ready to play, I wasn’t ready to get back on the court, so I decided to redshirt and try to resync my whole body.”

That decision to redshirt marked a turning point for Clifford. Once he made the call, it was bad, but it was settled—he could give getting better a real shot. Within weeks, Clifford linked up with Henry Degroot, his “guy off campus”: a massage therapist and strength and conditioning coach who serves as a performance and rehab consultant.

In their first meeting, Degroot told Clifford he could help. He was going to be able to move the way he was meant to move again. Degroot took a cumulative look at Clifford’s body, observed that the tightness in his hips put stress on his knees, and began breaking Clifford down to scratch, loosening his muscles and redesigning the way his body moved. Phase One was to get Clifford walking without discomfort again.

“I remember, like, the first week that I was able to get out of chairs without pain, I was like, ‘Oh crap, this guy actually might know what he’s talking about,’” Clifford said.

Clifford responded positively to the early treatment, and in conjunction with BC’s doctors they developed a plan. Phase Two meant pool exercises, rehab, and leg strengthening—for almost two years, Clifford had barely worked on his legs. With Clifford feeling increasingly better, it was time for Phase Three. Clifford got back on the court.

Sufficiently cooled off from practice, Clifford’s more relaxed at this point—his renewed appreciation for the complexity of the human body is clear, along with his sense of humor.

“I look at myself as a scientist now,” Clifford said. “It’s weird, over the course of the two years, I probably tried to get back like 20 times. There was probably like 20 separate times where I would rest, and rest didn’t really do anything to help the way that your body moves—I didn’t really get better, I would just try to get back and then it would hurt again, and I’d be like, ‘Crap, I can’t do this anymore.’”

But against all odds, Clifford is doing it. He’s a 22-year-old redshirt junior with no pain, two years of eligibility left, and the opportunity to play a vital role as Christian begins his attempt to turn BC men’s basketball around. There’s not a big place in the NBA for guys like Clifford with an injury history, but who knows—two seasons of high-level performances, and he could earn a flyer in some team’s training camp.

But after the last two years, Clifford’s become keenly aware of his career’s mortality.

“I’m acting like this is my last season,” Clifford said. “These are the guys I came in with, I’m a senior now in school, I’m already older than everybody. It’s kind of like, I want to act like this is my last season. Every day in practice, act like this is my last shot.”

Like every one of his teammates, Clifford wears a black and white wristband bearing the message “STAY POSITIVE” and “TRUST THE SYSTEM.” The irony of the message isn’t lost on him. He laughs, but swears he’s buying into Christian’s system 100 percent.

With a buzzed head and goofy smile, Clifford still looks a lot like he did freshman year, which is pretty similar to that 16-year-old kid wrecking high school basketball defenses on YouTube. He’s matured through the journey, though, made to appreciate the simplicity of side stepping, running, shuffling, jumping around the court, and slamming home dunks. Power Gym is empty at this point, and the interview finally comes to an end. All 7-foot-1 of Dennis Clifford stands up to leave, and he walks to the door.

No pain.

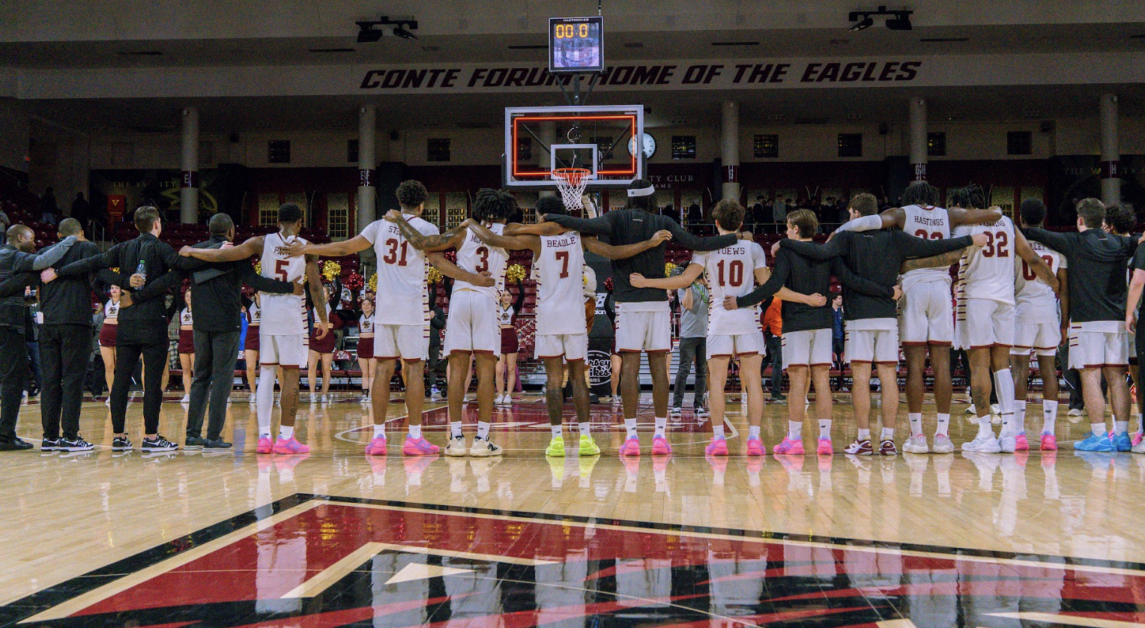

Featured Image by Emily Fahey / Heights Editor