For every story we have told, there are dozens we have yet to tell. For every story we have heard, there are thousands we have yet to hear. Some of these stories are unfolding now, while others have yet to happen. Still others are lost in time. One such forgotten story is that of Lou Montgomery.

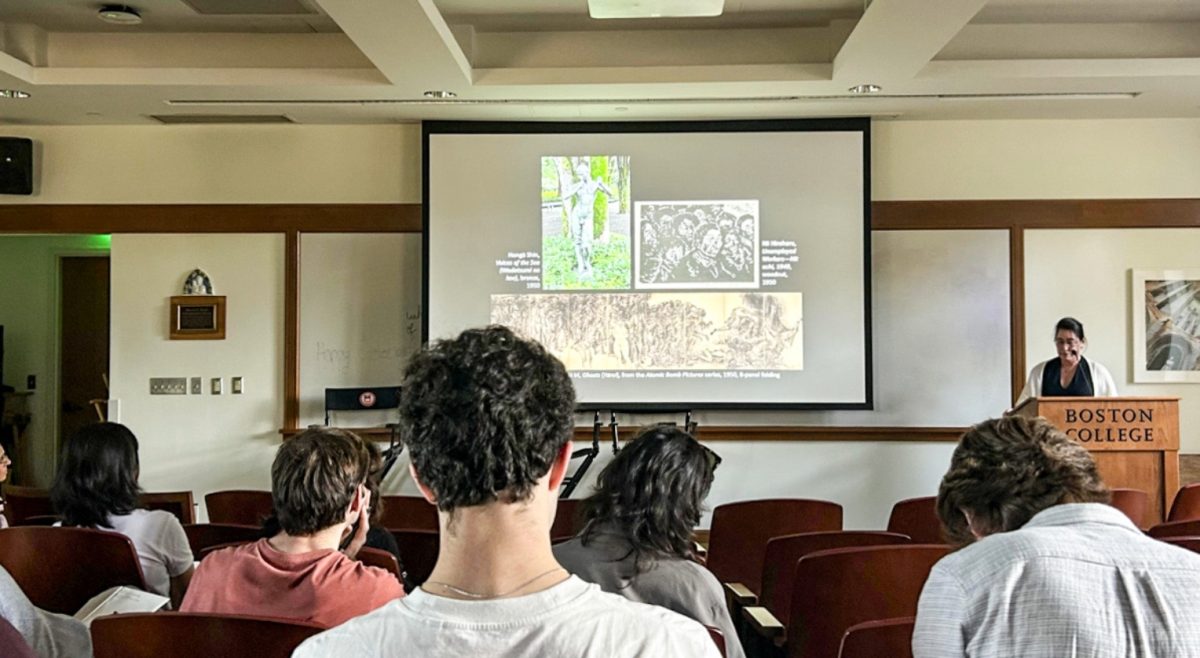

Lou Montgomery: A Legacy Restored is a film by MCAS Honors Program professor Susan Michalczyk. It follows the trials and triumphs of Lou Montgomery, Boston College’s first black athlete. Brimming with heartfelt testimonials, family accounts, and audio from Montgomery himself, the film speaks to both the successes and shortcomings of BC as Lou treaded on the untested grounds of integrated collegiate sports.

A native of Brockton, Mass., and a Brockton High graduate, Montgomery made his stature as an athlete clear. He was a state-athletics star and many schools recognized his potential. He was offered football scholarships from schools across the country, most notably UCLA, one of the most progressive universities of the time when it came to integrating sports. Going to UCLA would have made made him teammates with Jackie Robinson and Kenny Washington, the first black football player to sign with an NFL team. But instead of heading off to California, Montgomery chose to stay close to home and attend BC in 1937.

With so much talent, the Eagles during this time were quickly becoming a powerful football force. Under head coach Gil Dobie, Montgomery was put on the varsity squad after his freshman year. After the departure of Dobie, legendary head coach Frank Leahy stepped in to bring about a golden era of BC football, heavily involving Montgomery. During this historic era, Montgomery, a running back, shared the field with several College Football Hall of Famers, including quarterback Charlie O’Rourke and fullback Mike Holovak. Played to his potential, Montgomery was incredibly impressive. Under Leahy, Montgomery averaged just under nine yards a carry.

[aesop_gallery id=”112997″]

His fullest potential, unfortunately, may never have been realized, as the outside world pressured the team to make unfair concessions. Plagued by the “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” in which Southern schools would refuse to play unless the other team’s black players were not in attendance, Montgomery was often benched. During this time in BC football history, building a brand stood above upholding principle.

Montgomery’s absence did not go unnoticed, however. In the 1939 season, the Eagles’ only losses were against Florida and against Clemson in the Cotton Bowl, leaving the Eagles 9-2. Montgomery was absent from both games.

In the 1940 season, Leahy sought to flesh out other options in the offense, as he knew Montgomery would not be allowed to play when facing tough, Southern opponents. Leahy and the Eagles went on to finish the season with a win against Tennessee in the Sugar Bowl at 11-0 without Montgomery. This was the year BC stood as mythical national champions

But a large part of Montgomery’s legacy stands not on the injustices done against him as an individual player, but in his virtue as a teammate. Many of his teammates at BC also hailed from Massachusetts. Montgomery had played with them in high school and his absence in many games was seen as unfair by a bulk of the team. Despite this, Montgomery removed himself without protest, not wishing to inflict punishment on the rest of the Eagles because of Southern teams’ unwillingness to look past the color of his skin.

“Had he gone to UCLA, he would have found a more welcoming community with respect to race. […] His life would have been so very different,” Michalczyk said. “He would have had the chance to reach his potential and that is a loss not only for Montgomery, but for all of us.”

But Montgomery’s love of the game was far greater than the prejudice harbored in the hearts of others. During the pivotal seasons of 1939 and 1940, Montgomery proved himself a vital part of the program on and off the field.

These sentiments are beautifully explored in Lou Montgomery: A Legacy Restored. Rife with passionate, earnest reflection on Montgomery’s story in the BC community, the film is as much about what his story meant at the time as what it means today. In a critical, yet fair fashion, many interviewees in the film call into question the conflict between the Jesuit values of the University and the willingness to abide by the Gentleman’s Agreement. What real jurisdiction does an antiquated Southern prejudice have in the North? Certainly, when visiting teams in the South, Southern law took precedent, but Montgomery was also put on the sideline at home, facing visiting teams.

Sadly, principles were set aside to ensure BC could play ball at the highest level. Though racism and prejudice are forces that exist outside of one university, organization, or sport, people complicit in their effects warrant criticism. In BC’s case, Montgomery’s plight, as so many of the interviewees pointed out, is a blatant violation of Jesuit and Christian values and that these events represent, at least, a sorely disappointing moment in the University’s history.

This may be why Montgomery’s story is not widely known. We have always heard of Doug Flutie, Matt Ryan, and Montgomery’s contemporary, O’Rourke, but we seldom, if ever, hear about Lou Montgomery.

“As with so much in life, when there is pain or embarrassment or a sense of not having done something perfectly, most people and institutions prefer not to dwell on those moments,” Michalczyk said. “It’s human nature. And yet, unless we acknowledge the past, we are doomed to repeat it.”

The film will hopefully achieve acknowledgement and recognition of Montgomery in a wider sense. In 2012, Lou’s jersey was retired and honored in the Southwest corner of Alumni Stadium, but as the film is quick to point out, the discussion should not stop there. The film seeks to put a fire under the conversation and to achieve a greater sense of recognition of Montgomery.

Cai Thomas, MCAS ‘16, worked on the film as a co-producer, camera operator, and editor. After hearing about Montgomery’s story as a freshman, during the 2012 ceremony, Thomas was poised to learn more about Montgomery. Upon learning about the film project, Thomas quickly became involved. In addition to the production work, Thomas was instrumental in gathering the archival sources for the film. Speaking to the most compelling aspects of Montgomery’s story, Thomas said that listening to the audio and hear him speak about the discrimination he faced and about BC was one of the most profound and personal touches of the film.

Though the film, all those involved hope to institutionalize his memory and make it as common as other BC greats. Presenting Montgomery as an important pioneer in BC’s history is important for the University. This is in part the reason his story is being presented as a film.

“Art, the visual image, the music, the story, the narrative allows for a less threatening interpretation,” Michalczyk said. “It allows people to watch and process, and make connections in a way that would not work with simply listening or reading. The film is a great tool to get the idea out to people.”

Lou Montgomery: A Legacy Restored is, as the title suggests, an attempt to renew an interest in Montgomery’s story. Though the film does point out BC’s shortcomings, it does not wish to demonize the University. A Legacy Restored is a touching account of one man’s virtue in the face of adversity. In the audio logs from Montgomery, talking about his time at BC, one thing remained clear: in spite of all the troubles, his love of the game was strong.

“I hope people find inspiration in Lou’s story and consider ways that we can help make a difference, whether through a scholarship, a statue, yearly conversations, and dialogue, in ways that will result in positive changes on our campus and beyond,” Michalczyk said.

Featured Image By Susan Michalczyk

Neil Rice • Dec 24, 2016 at 2:29 pm

What took BC so long to retire Lou’s number ? Why did a Jesuit institution go along with the racist Gentleman’s Agreement when playing at home ?I guess winning football games was more important than doing the moral thing. BC needs to rename Alumni Stadium the Lou Montgomery Stadium to atone for their cowardly behavior . BC accepted Jim Crow in order to gain national prominence in football. A sad and pathetic chapter in the school’s history.

Kathy • Apr 4, 2016 at 4:31 pm

The retirement of Lou Montgomery’s shirt in Alumni Stadium came about in 2012 because of my brother Mark Dullea’s efforts. The film “Lou Montgomery: A Legacy Restored” likewise was spurred by his calling attention to Jim Crow laws affecting the North–specifically, a black football player not being allowed to play against Southern teams. Also see Mark’s website http://www.loumontgomerylegacy.com.

Mark Dullea • Mar 3, 2016 at 2:05 pm

http://www.loumontgomerylegacy.com (for more on the L.M. story)