Fred Kinsman earned his varsity sweater for Boston College men’s hockey as a sophomore in 1964. At the time, students had to wear sport coats and ties to class, but the pride Kinsman took in wearing his varsity sweater was strong enough to get him to bend the rules.

The instant he took his seat donning his newly minted varsity sweater in marketing class, though, the professor pointed Kinsman out of the crowd.

“Mr. Kinsman,” he said. “Stand up. You don’t wear the varsity sweater in my class.”

Begrudgingly, Kinsman, BC ’67, swapped his maroon and gold for a black sport coat and sank back down in his seat. Still, his pride remained.

There’s something about BC hockey that makes its players stand a little taller and play a little harder.

“It is the players, the culture, the standard of excellence that pushed each and every one of us to want to be the best at our craft,” David Emma, BC ’91, said. “The opportunity to compete and play alongside so many tremendous players is why BC produces so much talent.”

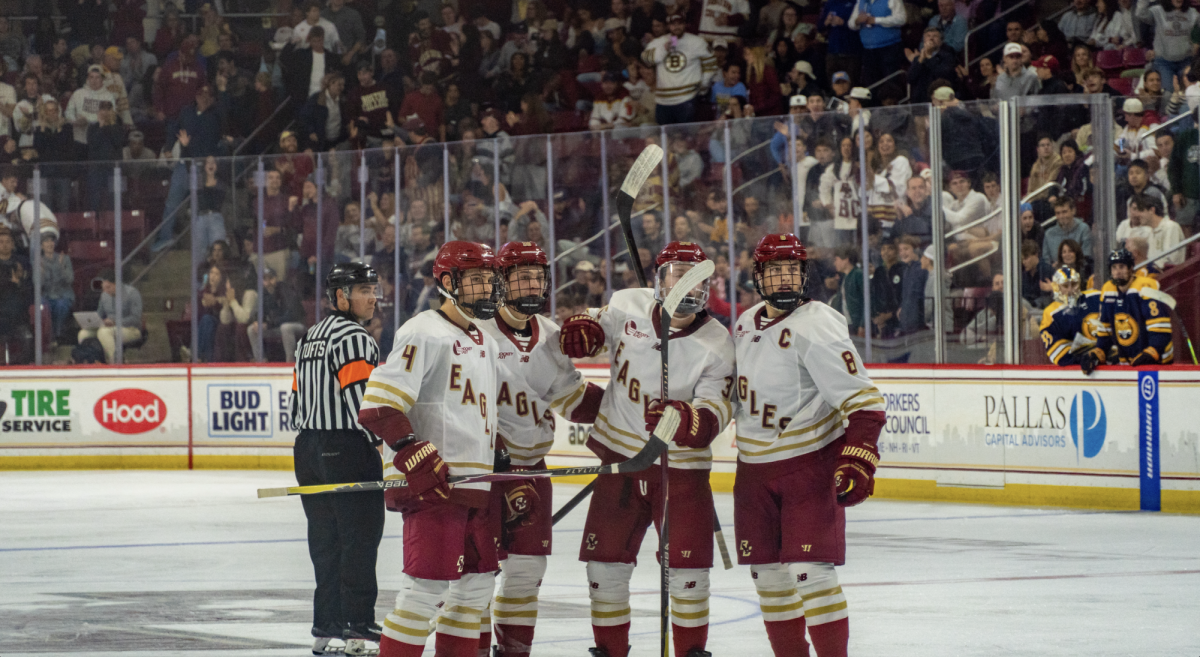

It helps that BC has had 99 seasons to develop that culture. The puck drops on BC’s 100th season this week, making it one of the most historic programs in the country and instilling in players both past and present a sense of unbreakable pride. A century of hockey, producing five National Championships, countless professional players, and some of the greatest moments in collegiate hockey history, has the power to do just that.

Finding Its Wings (1917–1940s)

In BC’s first season, it was one of just 11 collegiate hockey programs in the country. The team had existed informally for 20 years prior, but under head coach Robert Fowler, BC set out to write what would become an epic of college hockey history. The Eagles—a nickname the team didn’t go by until The Heights suggested it in 1920—went 2–1 in their inaugural season, but only one of those games came against a collegiate opponent: a 3–1 win over Boston University, setting the stage for nearly 100 years of crosstown rivalry.

After the first season, however, it took the story a few chapters to get going. Between 1918 and 1929, BC finished above .500 just five times. The Eagles had established a fledgling national presence, but it was still miles—and decades—away from reaching the glory days.

So when the 1929 stock market crash and ensuing Great Depression rocked the country, BC was left with no choice but to scrap the hockey team.

But what is a winter in New England without hockey? A short four years later, BC hockey made a less-than-triumphant return.

“After the close of the football season, a group of students intensely interested in hockey, and not wishing to look forward to a winter of athletic inactivity at the Heights gathered together to discuss plans for the revival of the winter sport at a college which has produced some of the most famous names in intercollegiate hockey history,” read a Heights article from January 1933.

The group of students persuaded the BC administration to bring hockey back to the Heights, and John “Snooks” Kelley, having played at and graduated from BC just three years earlier, agreed to coach. Kelley steered the Eagles in the right direction, finishing above .500 in every season but one in the first 10 years of his tenure.

But just as had happened the last time BC hockey began to gain traction, a major world crisis put a halt to its progress. Kelley temporarily gave up his coaching duties in 1942 to enlist in the U.S. Navy during World War II, where he stayed until 1946. The Eagles went on hiatus during the war from the end of the 1942–43 season until the beginning of the 1945–46 season. Kelley returned one year later, and without missing a beat, the Eagles were back on track.

The National Stage (1949–1965)

Kelley’s return became all the more triumphant when he brought with him the hopes of a National Championship. In 1948, the Eagles took their first trip to the Frozen Four, falling 6–4 to Michigan in the national semifinal. Though BC returned to Chestnut Hill without any hardware, Kelley and his team had set a precedent.

The next year, they made a return trip to the Frozen Four, this time besting Colorado College in the semifinal. After leaving the state of Massachusetts just three times in regular-season competition and heading into the postseason with a gleaming 17–1 record, BC looked unstoppable. The Eagles took home the title in the Northeastern Tournament, a precursor to the Beanpot, before taking on Colorado College. One day later, the “Kelleymen,” as The Heights dubbed the 1948–49 Eagles, narrowly edged out Dartmouth 4–3 in just the second NCAA Tournament of all time.

“The greatest ovation ever unloosed for the benefit of a national collegiate champion was given [to] the Boston College Hockey team when it alighted from the United Air Lines giant DC-6 Mainliner at 7:30 last Sunday evening,” said a Heights article following the team’s return to Boston.

But what the Eagles didn’t know at the time, after their first taste of national glory, was that they would face a 50-year drought. BC made four more trips to the Frozen Four over the next 12 years, but the semifinal round became its kryptonite.

Perhaps it was an attempt to break the pattern, or perhaps the Eagles wanted to expand their national presence, but prior to the 1961–62 season, BC made the move from independent to join the Eastern College Athletic Conference (ECAC). If the former was the goal, the conference move made no difference in BC’s national tournament success, as the Eagles once again fell in the NCAA Semifinal the next year.

Around that time, however, a few now-legendary names began to appear on the roster. BC was no longer a commuter school as it had been during the earliest days of the hockey program, but its roster remained New England–heavy.

“When we played … the only person on the team from out of state was Jimmy Mullen from Rhode Island,” Kinsman said with a chuckle. “It was all local players, you know, Melrose, Arlington, Norwood, Walpole, you know, Swampscott, Marblehead. It was all local kids.”

The same cannot be said for today’s team, as BC’s 2020–21 roster features two players from Ohio, two from California, and two from Canada. Recent BC rosters have also featured skaters out of Sweden and Finland, among others.

During his tenure, Kelley was known for his unconventional recruiting tactics, in which he would go up to high school players on the Boston Globe All-Scholastic list and ask them “What are you doing next year?”

One of the beneficiaries of that question was Jerry York, a product of BC High. After his freshman season on the Heights, Kelley called York, BC ’67, up to varsity, where he steadily became a stalwart of the Eagles’ rotation, and by the end of the season, had become a bonafide hero.

In overtime of the tournament’s first round against Harvard, Kelley opted to start his sophomore line—dubbed “the kid line” by Jocko Connolly, longtime writer for The Boston Herald—featuring York and Kinsman. The pair broke out on a 2-on-1, and a quick fake from Kinsman sent Harvard defender Bobby Clark the wrong direction, and he posited the puck to York for a quick finish.

“That was one of the bigger great moments for myself at Boston College,” Kinsman said.

That year, the Eagles won the ECAC and made yet another trip to the Frozen Four. There, BC upset North Dakota in the semifinal round before falling to Michigan Tech in the title game, leaving the 1949 banner alone in the rafters for yet another year.

After falling to Michigan Tech, BC began an unprecedented slide. By the time the 1970–71 season rolled around, BC had fallen below .500 for the first time since 1945–46, when the Eagles played just three total games and lost two of them.

A Familiar Face Returns (1972–1992)

As what looked like a drought in the Eagles’ success began, BC called on a familiar face, one who knew how to win at BC. And who better than a member of the 1949 National Championship team?

It was in that National Championship game that then-sophomore Lenny Ceglarski, later known as Len, began to make a name for himself. His second-period goal put the Eagles up 3–2, before they went on to win 4–3 over Dartmouth.

Ceglarski returned to the Heights in 1972 as BC’s head coach after Kelley’s retirement. His 20-year coaching career was one of the most transformative stints in BC history, as the Eagles made nine trips to the NCAA Tournament in that span. But perhaps Ceglarski’s biggest move at the helm was to oversee a jump from the ECAC to Hockey East when the conference first began in 1984.

That move paid off for the Eagles, as from 1984 to 1992, BC took a trip to the NCAA Tournament six times and finished first in Hockey East in all six of those seasons.

Leading the charge in BC’s earliest days as a member of Hockey East was Emma, who was named to the All-Hockey East Rookie Team in 1987–88.

“I tried to play every game like it was the last game. I never took one game for granted,” Emma said of his rookie season. “I always felt like you have to earn respect each and every night. This was the culture I tried to build at BC in my four years.”

Respect appeared to come easily for Emma, as by the time he was a senior, Emma was BC’s all-time leading scorer with 239 points (112 goals, 127 assists) across his four years. After leading the Eagles with 35 goals and 46 assists his senior year, Emma became the Eagles’ first Hobey Baker Award winner, honoring the best collegiate hockey player in the country.

“Winning the Hobey Baker was a huge exclamation point to my time at BC, but I would have given anything for a National Championship, or a Beanpot [title],” Emma said.

As talent-laden as BC’s roster was at the time—the team that preceded Emma’s freshman year produced seven future NHL players—the elusive National Championship remained just out of reach. That’s not to say that BC was without support or without big wins during Emma’s career. In fact, the opposite was true.

During the 1989–90 season, Emma’s junior year, the Eagles hosted Minnesota in a best-of-three series during the NCAA Tournament. After splitting the first two games, Emma scored two seconds into the third game off the opening faceoff en route to a 6–1 win, earning a trip to the Final Four. Conte Forum, built just one year prior, was rocking.

“Students and fans stormed the ice after the huge win, and Bill Guerin grabbed a huge BC flag and was skating around the ice in celebration,” Emma said. “The atmosphere that night was probably one of the most incredible experiences of any night at BC.”

The Promised Land (1994–present)

Though Ceglarski’s tenure rocketed BC even further into the stratosphere, the program was rapidly approaching 50 years of National Championship drought. After two years of interim coaching following Ceglarski’s retirement, BC finally found its ticket to the promised land in the form of York.

It’s hard to know if Chet Gladchuk, Jr., the athletics director at the time, knew the gravity of the hire he had just made. He didn’t know that York would lead his team to 11 Hockey East regular season titles (or, 11 so far). He didn’t know that York would become the winningest hockey coach in NCAA history. He didn’t know that York would deliver four National Championships in his first 20 years at the helm. How could he have?

All he had was York’s track record. Seven years at Clarkson and 15 at Bowling Green—including one National Championship at the latter—hinted at greatness to come. The immense scale of that greatness, however, would be unveiled over the next three decades.

After accepting his dream job at his alma mater, York hit the ground running. It took three seasons for the Eagles to make the NCAA Tournament under York, but in the spring of 1998, the Eagles began to see what was to come.

In 1998, the Eagles fell in the National Championship. The next year, they lost in the national semifinal, and the year after that, they lost in the National Championship again. It was only a matter of time before the trophy returned to Chestnut Hill.

The next year, the 2000–01 season, the story began to write itself. An all-star roster featuring Brian Gionta, Brooks Orpik, and Chuck Kobasew, among others, propelled BC to its first regular season conference title since York took the reins.

And the wins kept coming. BC won the Hockey East Tournament in efficient fashion, earning an automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament for the fourth time in as many years. Wins over Maine and Michigan sent the Eagles to the National Championship game, setting them up against North Dakota, which had devastated BC in the title game one year prior.

“It could’ve been a lot easier,” a Heights article following the game read.

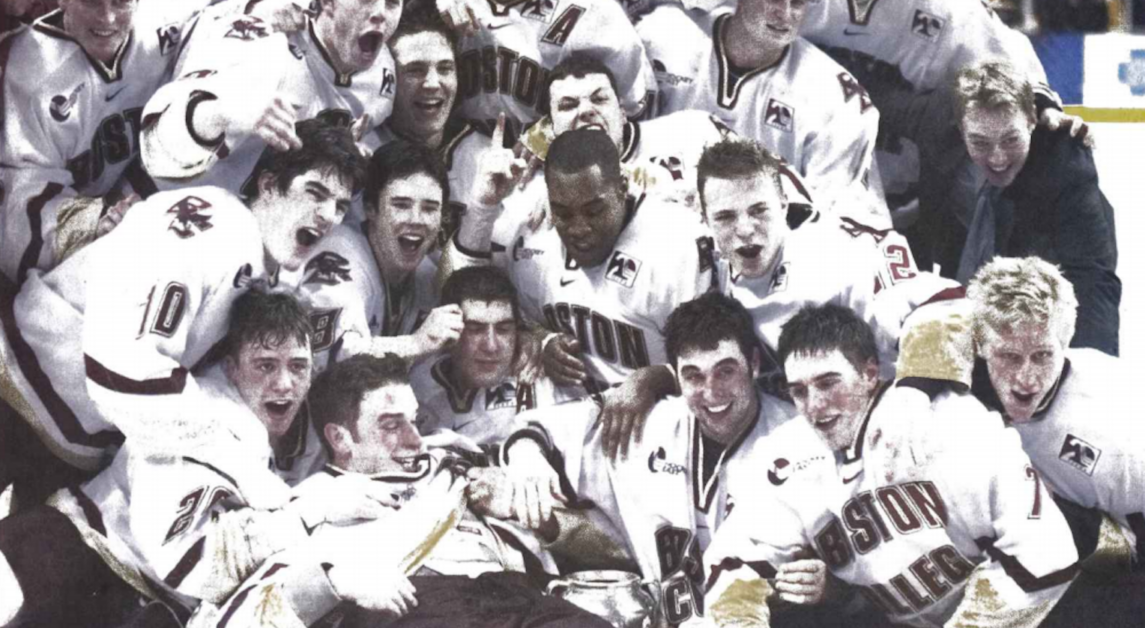

But it wasn’t. Nursing a 2–0 lead in the third period, the Eagles watched their first National Championship in 52 years begin to slip through their gloves. Instead of BC cruising to victory, North Dakota forced overtime, and it took a sudden-death goal from Krys Kolanos to clear the benches and send BC home with hardware for the first time in five decades.

“That emotion, what happened that night, it fuels us,” York said. “I want to do this again. I want the same players, coaching staffs to experience the same thrill of that. Because there’s a lot of nights you don’t win, and to be able to have that, and bank that, is pretty important for us.”

Students back on the Heights fled from their residence halls and took to the mods, tearing down fences and throwing beer cans all the way, according to a Heights article at the time. Their celebrations were warranted, given the seemingly eternal nature of the drought that BC had finally ended.

“We had gone 50 years without winning a national title, and that [2001 title] was a breakthrough that clearly helped us win the next three here at BC,” York said. “But the first one’s always difficult.”

Suddenly, the floodgates were open. York and the Eagles won three more National Championships in the next 11 years: 2008, 2010, and 2012. He hit the biggest milestone of his coaching career in Amherst in 2016, becoming the first coach in collegiate hockey history to reach 1,000 career wins.

“It’s not part of my fabric, it’s not part of my makeup,” York said after that milestone win. “You leave your ego at the door. You’re a family.”

In the nearly three decades since York was named the Eagles’ head coach, he has produced two Hobey Baker Award winners (Johnny Gaudreau in 2014 and Mike Mottau in 2000), one Mike Richter Award winner (Thatcher Demko in 2016), one Tim Taylor Award winner (Alex Newhook in 2020), and countless other individual award winners and professional players.

“Jerry teaches them the right way to do things,” Kinsman said of his former linemate. “And around the NHL, they’re looking at these things. They’re always talking about Jerry this and Jerry that.”

It’s a recent phenomenon that college hockey has become a stepping stone, rather than a destination. Many players have an NHL roster spot awaiting them before they even set foot on the Heights, and York largely expects to only have his best players for two or three years.

“I think when he recruits them he’ll sit down with these guys and say ‘I’ll understand if you want to leave after two or three years,’” Kinsman said. “‘But I hope you don’t leave, because that next step could be that National Championship.’”

Featured Image Courtesy of BC Athletics

Other Images Courtesy of BC Athletics