With the novel coronavirus bringing much of American life to a standstill, Boston College has now been practicing remote learning for weeks. Although classes have only been moved online for the remainder of the semester, students have already begun to wonder if they will be able to return to Chestnut Hill for the fall semester.

The answer to that question is still unknown, but new developments are slowly giving clarity to the issue.

“I think we need to get through May. I think we need to start into June and see what happens with our dynamics,” epidemiologist and nursing professor Nadia N. Abuelezam said. “I think people will have a much, much better view of what will happen in June.”

Even with the uncertainty about timing, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington recently released a model that predicts no new deaths related to COVID-19 after June 14, but does not include the fall.

“We could have smoldering cases and reintroductions [of the virus] going through the summer into the fall even into next winter when it’s hard to predict,” Director of BC’s Global Observatory on Pollution and Health Philip J. Landrigan said. “If people are coming in from overseas, there’s the potential for reintroduction, and that’s relevant of course to our student body at Boston College because we literally get students from all over the world.”

The expectation is that subsequent peaks of infections in the United States should not be as large as the one that is currently being experienced, Director of the Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases Anthony Fauci said at a White House briefing on March 30. But like all predictions about the novel coronavirus, nothing is certain.

“We’ll have recurrent bumps as new introductions come in, but I don’t think there’ll be a huge second wave. Unless there’s one thing, and that is if the virus changes,” Landrigan said. “If it changes in such a way that people who are immune are no longer immune, in other words the virus develops new biological factors that enable it to evade the antibodies that people will have developed.”

In addition to the complexities that public health officials face when it comes to choosing when and how to reduce social distancing measures, college campuses pose a challenge unto their own.

“I definitely think we have to be very intentional about thinking about how we might return to campus, how students can live on campus safely, and I think also thinking about how we can reduce risk for students is going to be really important,” Abuelezam said. “You’re living in community, you’re studying in community, so figuring out creative ways to stay in that community while also being safe I think will be a challenge for college students as well.”

If the United States reaches a place where testing is ubiquitous, transmission of the virus is at a very low level, contact tracing is robust, and hospital capacity is satisfactory, then stay-at-home orders will begin to be lifted. When that happens, life will not return to normal instantly—it is likely that people will still be encouraged to practice some form of social distancing and that large gatherings would still not be permitted, University of California Irvine professor Andrew Noymer told The Atlantic.

Staggering employees’ return to work and limiting the size of meetings are ways to work through pandemics, according to the Society for Human Resource Management. But these recommendations, like others being proposed, are not conducive to college life.

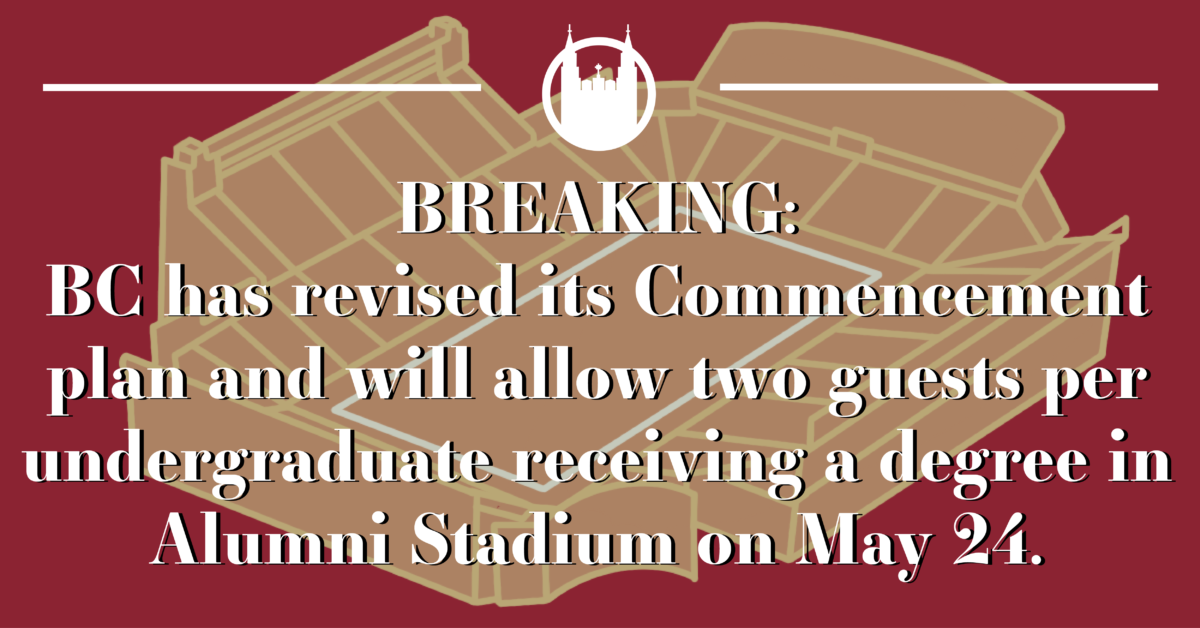

Come August, about 14, 559 students would converge on BC’s 373 acre campus. There they would live tightly in residence halls, attend classes in the same academic buildings, and eat together in dining halls. Instituting social distancing measures would require considerable intention from both administrators and students.

Large club meetings and weekend parties would likely present concerns, similar to those of some conferences and college administrations with regard to filling stadiums come football season.

Associate Vice President for University Communications Jack Dunn did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the University’s ongoing plans in light of the novel coronavirus.

Despite these unknowns, Fauci said on Tuesday at a White House briefing that he feels optimistic schools will be open come autumn.

“I’m humble enough to know that I can’t accurately predict, [but] that by the time we get to the fall, that we will have this under control enough that it certainly will not be the way it is now, where people are shutting schools,” Fauci said during a White House briefing. “My optimistic side tells me that we’ll be able to renew, to a certain extent, but it’s going to be different, remember now, because this is not going to disappear.”

1. Trend Lines

Understanding the general trend line of the disease’s progression in the United States is the best indicator of how COVID-19 will continue to have an impact in the months to come.

“The single most important thing to watch in terms of getting a sense of where this thing is headed and specifically where things will stand next August … is the trend line on the number of cases in the United States,” Landrigan said.

Landrigan emphasized the importance of primarily using American data to predict future outcomes in the United States, instead of data from other regions that may have peaked before the United States, such as northern Italy, due to the differences in size and scale.

While the outbreak in Italy dramatically affected a few targeted regions, Landrigan said he believes that the United States will see a delayed spread of the virus over different geographic regions within the country.

“I think what we’re already beginning to see, in fact, is that the epidemic is hitting different places at different times,” he said. “Not surprisingly, it started in the big port cities that have a lot of aircraft from Asia, Seattle [and] New York.”

COVID-19 has also been compared to the Spanish Flu of the early 20th century, mainly because it also began in spring, but receded over the summer, only to return powerfully in the colder months. But this comparison is likely flawed, according to Landrigan.

“I don’t think we’ve kind of seen this seasonal ping pong. Also the fact that it’s happening in Brazil, Argentina,” he said. “The fact that it happened in Singapore, which is a profitable country four degrees off the equator, says to me that the summer weather doesn’t kill this virus, because after all it was summer down in Brazil when this thing got started.”

Abuelezam said she does believe the coronavirus will become seasonal, similar to the other seasonal flu viruses that doctors already vaccinate for come the fall.

“I do think, as I mentioned, that there is likely some seasonality, but I also think that a reemergence in the late summer, early fall will also [be] likely,” she said.

2. Antibody Testing

The ability to perform antibody testing on a large scale could be key to understanding where the disease is geographically, and being able to better discern who is vulnerable to it and who may have developed immunity.

“Antibody testing or a serology test [a test to measure antibodies in the blood] would be really helpful because if you could have everyone tested serologically, you could determine who already has antibodies present, and then that might also allow you to have a targeted response,” said Abuelezam. “So you could for example say, ‘All right, if you have antibodies, you can go back to work. We think you’ll be protected.’”

Both Abuelezam and Landrigran said that while no data on the presence or strength of antibodies is entirely conclusive, scientists believe that after someone successfully fights off COVID-19, they possess antibodies to potentially deal with it again.

“The antibodies begin to go up, and they continue to go up for a period of some weeks, and then they stabilize and everybody … hope[s] that those antibodies that are now developing in people are going to give them lasting immunity,” Landrigan said.

This kind of testing is already being implemented in some U.S. cities.

“I think in Boulder, Colorado, they’re testing the entire city or county serologically to sort of try and assess the extent of the epidemic,” Abuelezam said. “So I think it’s already being done. The question is can we do it for a more widespread population.”

The ability to conduct widespread antibody testing, possibly on the entire student population at BC, could be important for relaxing certain social distancing measures and allowing students to return in the fall.

“Once the antibody test is widely available and people can get tested quickly, it will tell you in a very short period of time whether a person is protected or not,” Landrigan said. “That will enable administrators to make rational decisions on who they can put back into social circumstances and who they have to continue to protect.”

3. Contact Tracing

Robust contact tracing will also be an important aid in allowing social distancing measures to be relaxed. Contact tracing is the practice of alerting and isolating any person who has had contact with an infected person.

This practice helps to slow the spread of the virus and allows people to isolate before they begin to show symptoms. If it is able to be executed on a large scale, it could have a significant impact in reducing the spread of the virus.

4. Therapeutics

The best chance for altering current social distancing timelines and returning to a normal way of life is a therapeutic, according to Landrigan. A therapeutic is a medical treatment that would reduce the severity of symptoms from COVID-19, thus reducing the strain on hospitals and the risk of death.

“I understand that there are several clinical trials, more than several, quite a number of clinical trials, going on around the country right now, or where people in medical schools and academic centers are trying out different drugs,” Landrigan said. “I haven’t seen any definitive results yet, but I’m pleased that they’re working on this and hope that something comes together that would be the silver bullet.”

There are common therapeutics in use today, such as Tamiflu to treat the seasonal flu or antiretroviral therapy, which consists of a combination of antiviral drugs, to treat HIV.

“You have to get them into people at the first sign of illness before the illness is really ramped up, or put it another way, before the virus load in their body gets too heavy. You give them the antiviral agent, and it knocks down the viral count,” Landrigan said. “It basically gives them much milder elements than they would have otherwise had and presumably makes them a lot less contagious than they would otherwise have been.”

If a therapeutic was to be proven widely effective and accessible for the population, the current timelines and projections may be revised to allow for a quicker reduction in social distancing procedures, according to Landrigan.

Featured Image by Ally Mozeliak/Heights Editor