2024 marks the greatest electoral mobilization in human history, with over two billion voters participating in democratic processes in 70 countries, according to Jonathan Laurence, professor of political science at Boston College and director of the Clough Center for the Study of Constitutional Democracy.

Still, Laurence added, there is also a growing fear of threats to democratic mechanisms both in the United States and other polarized nations around the world.

“So we seem to stand, if not [at] a precipice, then certainly at an inflection point, which we find while at a dangerous crossroads of renewed nationalism and, of course, growing economic inequality,” Laurence said.

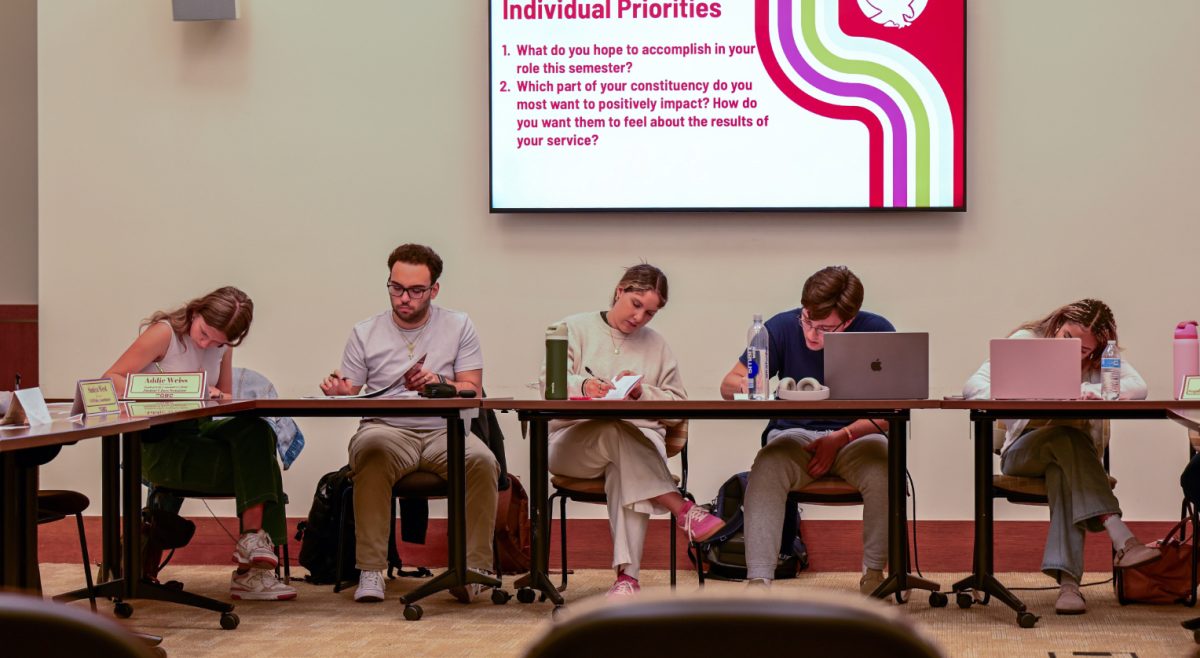

The Clough Center presented “What Comes Next? Assessing a Year of Elections” on Thursday evening to reflect on the present moment in political history and its implications on the future of democracy worldwide. The event was moderated by Laurence and featured Lauren Honig, David Hopkins, Sheri Berman, and Rahsaan Maxwell, all professors of politics at their respective institutions.

According to Berman, professor of political science at Barnard College, a key trend in both the United States and Western Europe is the growing success of right-wing populist parties, fueled by a rightward shift among young and working-class voters.

“There were elections for the European Parliament in June, and here, right-wing populist parties continued to gain strength,” Berman said. “They had won significant victories in the last election, in 2019. In these elections in June, they increased their vote share even more.”

Berman also highlighted the increasing focus on economics and immigration in voting.

“On both sides of the Atlantic, economic issues are top voter concerns,” Berman said. “But on both sides of the Atlantic, we’ve also seen the rising importance, the rising salience, of immigration.”

Maxwell, professor of political science at New York University, discussed the increasing prominence of immigration as a key issue in elections.

“It’s not as simple as saying that people are in favor of immigration or opposed to immigration,” Maxwell said. “There are lots of distinctions in there.”

Attitudes towards immigration, specifically among Western Europeans, have changed over time, according to Maxwell.

“Support for immigration is actually much larger than many people realize, and opposition is even smaller,” Maxwell said. “But over time, it’s become more concentrated, which gives it political power.”

Honig, associate professor of political science at BC, provided her perspective on the role of democracy in Africa, focusing on developments regarding electoral authoritarian regimes, where only the incumbent party wins elections, and electoral democracies, where incumbents do lose.

“I also want to point out here that, as Professor Lawrence had talked about, a pattern of dissatisfaction with the status quo related to incumbents losing this recent year, and we’re seeing that on the African continent as well,” Honig said.

Honig said that elections in which the incumbent loses may actually be a positive sign for the country.

“Incumbents losing elections is actually a sign of consolidation and of the democratic process working,” Honig said.

Hopkins, associate professor of political science at BC, said voters tend to emphasize the “short-term factor” of the economy, instead of recognizing that inflation belongs to a larger global pattern.

“Voters are mad about the economy,” Hopkins said. “Most of all, when people are asked about what they don’t like about the economy, it is because the inflation is bad, and they blame the incumbent Democratic party for that.”

In the long-term, the growing shift to the left among college-educated Americans, which he refers to as the “diploma-divide,” represents a larger educational trend worldwide, Hopkins said.

“The separation between the parties of the left and the parties of the right more and more separates well-educated, culturally progressive, and globalized parties from nationalist and less-educated parties,” Hopkins said.

Laurence asserted that democracy is associated with long-term economic and human development, and the benefits of constitutional democracy are largely undetermined.

“While electoral results are highly volatile and uncertain, we do hold some certainties about the benefits of constitutional democracy,” Laurence said. “It’s also in that spirit that we decided here at the Clough Center to plan and dedicate this year’s theme to envisioning democratic futures.”